The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Sibelius Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

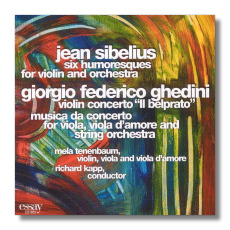

Jean Sibelius / Giorgio Federico Ghedini

Works for Violin & Orchestra

- Jean Sibelius:

- Two Humoresques, Op. 87 *

- Four Humoresques, Op. 89 *

- Giorgio Federico Ghedini:

- Violin Concerto

- Musica da Concerto for Viola, Viola d'amore & Strings

Mela Tennebaum - violin, viola, viola d'amore

* Pro Musica Prague/Richard Kapp

Czech Philharmonic Chamber Orchestra/Richard Kapp

Essay CD1075 58m DDD

Summary for the Busy Executive: Three finds.

Sibelius catches flak for his long decline into alcoholism and creative silence, during which he completed and then destroyed what would have been his eighth symphony. He also takes heat for the plethora of short works in his catalogue, as if his symphonic cycle, string quartet, violin concerto weren't enough to justify his stature. However, many critics don't recognize that an artist needs to eat. Sibelius wrote a lot just to support his family. The humoresques are late examples of this, written, I believe, before the Finnish government granted the composer a lifetime stipend. But as Dr. Johnson remarked, "Only a fool never wrote for money," and commercial success doesn't preclude artistic success. These six miniatures, averaging a little over three minutes apiece, make an effect that belies their length. One senses not only a great miniaturist, like Grieg, but a great symphonic mind (something very few ever accused Grieg of) working in little. The effect is heightened when you hear all six humoresques together. Here and there one catches little hints of the violin concerto, and one soon realizes that, notwithstanding his architectural smarts, Sibelius's art, like Elgar's, has this kind of miniature at its heart.

Ghedini, on the other hand, is practically off the radar. He's better known as Berio's teacher than for his own music. I'd heard only one other piece, for wind quintet, before these two string concerti. On the basis of all three works, I'd call him a Stravinsky-Hindemith neoclassicist, although like most of his tribe, he doesn't ape his models. He has something of his own to say. The composer officially lays out his violin concerto "Il Belprato" in five short movements, and like the Sibelius, each one averages out to between three and four minutes. However, in performance, it really comes down to three movements. In aesthetic, they remind me a lot of Vivaldi's violin concerti. That is, they don't scale heights or plumb depths, but they do exhibit an exceptional elegance and take on the energy of dance. The first movement, the longest, is one of those chattering Vivaldi allegros. What I call the middle movement and Ghedini formally splits into three is a gavotte, "with interruptions." That is, the gavotte switches to a vivace, which dissolves into a brief, though affecting, adagio. The finale blows off steam. The music speaks directly and without inflation.

The Musica da Concerto, in one large movement, calls for a viola soloist to switch to viola d' amore about halfway through. This is harder than it sounds, since one often tunes (and fingers) a viola and viola d' amore differently (the viola d' amore has three more playable strings). For one thing, the viola d' amore has no standard tuning. The standard viola tuning is c g d' a', while the most common tuning nowadays for viola d' amore is a D-major chord: a d a d' f#' a' d'. In addition, the instrument has seven more strings, not played, but which supposedly vibrate sympathetically. From a recording, I have seldom heard this effect, except as a nasty little buzz, even with earphones. As for the work itself, in general, it eschews the straightahead neoclassicism of "Il Belprato" for greater psychological penetration. The phrases are longer, twistier and more searching - more "Romantic," if you will. Even the volatile sections don't have a dance symmetry, often because they change character too quickly to establish one. The concerto consists of a series of builds and fallbacks. Time after time, Ghedini increases the energy only to let out the steam, usually with a soloist's recitative. The work sounds all over the place, as if even the composer doesn't know where we will end up, but this is illusory. Ghedini writes very tightly, even more so than in the violin concerto. However, the basic material belongs to an altogether higher level of complexity. This takes at least a couple of hearings to begin to hear the transformations. As in the concerto, Ghedini confines the accompaniment to strings only, but what a wealth of color and texture he comes up with! The viola d' amore, a wonderful instrument for playing chords, adds to the richness and power of the sound.

I've been a fan of Mela Tenenbaum's for many years - as far as I'm concerned, a musican of formidable intelligence and fire. She's always worth listening to - whether in violin monuments like the Beethoven concerto or the Bach solo violin music, modern music off the beaten track (like Ghedini and Klebanov), or even a Kreislerian encore. Kapp has served her as a very sympathetic accompanist. It's as true of this CD as of all their others. The Ghedini tracks come from live performances. They haven't been pristinely edited. You do hear a little audience stirring and rustling, and there's a brief moment in the Ghedini that I can best describe as "scrambling," as orchestra and soloist try to co-ordinate their rhythmic feet. However, that shouldn't put you off, especially since Ghedini is a composer more people should know, and the Sibelius is just downright beautiful.

Copyright © 2005, Steve Schwartz