The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Nielsen Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

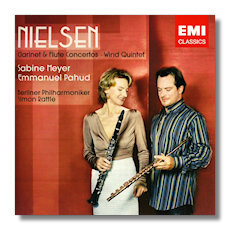

Carl Nielsen

- Clarinet Concerto

- Flute Concerto

- Wind Quintet

Sabine Meyer, clarinet

Emmanuel Pahud, flute

Stefan Schweigert, bassoon

Jonathan Kelly, oboe & cor anglais

Radek Baborák, French horn

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra/Simon Rattle

EMI Classics 3-94421-2

Simon Rattle first conducted the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra twenty years ago and has been their principal conductor since 1999, although his first concert in that capacity wasn't until 2002. It's not always been an easy relationship, of course, but some excellent recordings have emerged, often of repertoire that makes the most of both parties' strengths. So it is with this appealing collection of the Flute Concerto (FS119) and Clarinet concerto (Op. 57, FS129) by Nielsen, other recordings of which composer by Rattle are not exactly thick on the ground. But the most substantial piece in terms of length on this disc is Nielsen's Wind Quintet (Op. 43 FS100) using the same flute and clarinet soloists (Emmanuel Pahud and Sabine Meyer respectively) as in the two orchestral works with the addition of Stefan Schweigert (bassoon), Jonathan Kelly (oboe, cor anglais) and Radek Baborák (french horn).

Although Nielsen's very first instrument was the violin, by his teens he was playing bugle and trombone in the Odense regimental band. Later, after completion of the Fifth Symphony, Nielsen was inspired to compose a wind quintet in the style of Haydn and Mozart after overhearing musicians rehearsing the latter composer's "Sinfonia Concertante". At first intended to be light in tone and purpose – and light in composing commitment and requirements after the labors and rigor of his Fifth Symphony – the wind quintet eventually became much more substantial. It has two long outer movements, a chatty allegro, albeit with the characteristic ostinati and little running rubato phraselets for each instrument; and a concluding theme and variations lasting over ten minutes. And a darker, more sallow minuet and prelude as second and third movements. Although these total barely eight minutes together, they contain intense music, particularly the "Praeludium: Adagio" which utilize a somewhat somber Lutheran hymn written by Nielsen and requiring the substitution of the more lugubrious cor anglais for the oboe. So, although this has the impact initially of a somewhat unobtrusive and gentle work stirring no deep waters and breaking no new ground, it is tuneful, full of contrasts and color. Above all, it quietly achieves the objective of making a convincing and gratifying whole from the colloquy of actually six wind instruments. This aspect would be missed and its lack felt strongly were it not for the expert playing (clean, fresh, enthusiastic and melodious) of the soloists. Their articulation and sense of ensemble are exemplary. The recording and acoustic complement the emphasis necessary for the liquid and airy timbres of the instruments to hold Nielsen's conception together from beginning to end.

Composition of the wind quintet had a profound and positive effect on Nielsen: he described the way he now thought of orchestration – as if he were inside each instrument. The work itself was a success at its première and prompted him to plan to write a concerto for each member of the Copenhagen Wind Quintet. Alas he died (at the early age of 66) before being able to finish other than the flute and clarinet concerti; it is they which we hear as the first six tracks (the former is in two movements only; and was recorded in concert) on this seventy-minute CD with Rattle and the Berliners. What this does have as a performance, though, is the depth, the philosophical understanding, necessary for this lively piece not to be mistaken for mere fireworks.

The Flute Concerto was written, in fact, for Holger Gilbert Jespersen, a francophile with a predilection for refinement and delicacy. This is reflected in the smaller orchestral forces for which Nielsen wrote, the light tracery of some of the flute's key lines and the pared fingernail daintiness. Of intrusive and surely leg-pulling contrast is the middle of the first movement with the arrival of a timpani-accompanied bass trombone, which also gets the chief tune in the work's peroration. This performance with such streaks of humor and controlled deflation clearly benefits from being recorded live in the Berlin Philharmonie; the players are in tune with both the nuances and the punches not pulled by Nielsen. It's an extrovert and genial work, not a moment too long, nor a sound layer too thick, though in places (the fortissimi and tutti in particular) Pahud's attack on this recording is a little dulled, almost; he's never out of control, nor seems to feel the need to "compete" with the orchestra. But his negotiations of the intricacies of the solo writing are not quite so supple or agile as they might be. In the quieter passages, in compensation, his flute sound is less brilliant and more subtle. Though by the nature of the piece, this is not the place for the flute to charm or seduce. By the end, you're left feeling that Nielsen has wrenched the instrument out of Pan's hands and subjected it to some pretty tough treatment, which it's survived admirably. That is the strength Pahud (born of Swiss and French parents in 1970, he was principal flautist with the Berlin Philharmonic under Abbado until 2000) brings out.

Meanwhile the Clarinet Concerto presents other and very real challenges: the clarinet part is notoriously difficult (its dedicatee, Aage Oxenvad apparently complimented Nielsen on the standard of his own clarinet virtuosity if such was the kind of composition he produced for the instrument) and accounts for a diminished uptake in the repertoire. Nielsen seems to have had an ambiguous (and slightly frustrated?) attitude to the clarinet. In particular "troll like"… mercurial, changeable, not to say inconsistent in delivering beauty and coarseness in quick succession. And this pervades the concerto; there is a Nielsen standby, the snare-drum; there is bravado; impishness; a hint of melancholy perhaps borne of Nielsen's perception that such qualities are present with such a usually otherwise elegant instrument. And indeed it is kind of resignation, submissive melancholy that pervades the closing passages – and one's overall perception – of the concerto. Sabine Meyer (who was born in 1959 and was notably the first female member of the Berlin Philharmonic) is well up to conveying what Nielsen surely intended; she produces, under Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic, a performance that satisfies and stimulates. Whether she quite has as much expressionist exuberance, anger indeed, as Martin Fröst has on what must still be the front-runner recording on BIS 1463 with Vänskä and the Lahti Symphony Orchestra is open to doubt. The clarinet concerto is more discursive, less direct in thematic development and generally more speculative than that for the flute. These are strengths of Meyer's, although in places (two to three minutes into the third movement, for example) her somewhat gentle clarinet tone seems hard put to distinguish itself above the orchestral sound.

This is a nice little collection representative of Nielsen's love of the woodwind family in chamber and orchestral contexts (indeed there are passages in the quintet's last movement that sound almost orchestral). It's a good foray by Rattle into a repertoire that should enrich his appeal simply because the palette and world of Nielsen are so self-contained, self-confident and (in the nicest way) self-referential. The liner notes are simple and it's Pahud and Meyer who are illustrated on the CD's cover. Although one may have glancing doubts less about the interpretation of the music (Nielsen's purity, unself-indulgent and yet very individual tonal world is well painted here), there are places in the concerti when the balance between soloist and orchestra and the freedom of the soloists to linger on the more expressive points and passages are denied by a somewhat insensitive orchestral brief. Nevertheless, recommended.

Copyright © 2007, Mark Sealey