The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Britten Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

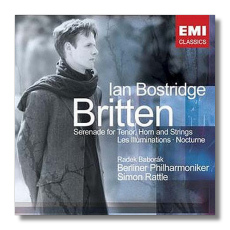

Benjamin Britten

- Les Illuminations, Op. 18

- Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings, Op. 31

- Nocturne, Op. 60

Ian Bostridge, tenor

Radek Baborák, horn

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra/Simon Rattle

EMI Classics 558049-2 DDD 74:55

It is impossible to hear this music without remembering tenor Peter Pears, Britten's lifelong companion, but Bostridge does his best to make us forget him with singing of unearthly beauty and with probing interpretations.

Bostridge, Rattle, and the Berlin Philharmonic performed these three song-cycles at the Salzburg Easter Festival and recorded them soon after in Berlin. Bostridge is no newcomer to Britten's music. In 1994, his operatic debut was as Lysander in A Midsummer Night's Dream. A few years later, he recorded the Serenade for tenor, horn, and strings with Daniel Harding (also released on EMI), along with Our Hunting Fathers. Why he chose to make a second recording of this work in so short a time probably has to do with the intensity of his musical relationship with Rattle, and with his increasing maturity as a singer.

Pears did not have the most conventionally beautiful voice, particularly when he got around to recording these works in stereo. His voice and manner of using it were so characteristic that sometimes the song threatened to disappear behind the enormous presence of the singer. (This probably sounds worse than it actually was. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau's and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf's singing make a similar impression on me.) Bostridge has been gifted with an instrument that is more capable of alluring the listener, and furthermore, he can make himself "disappear" more readily than Pears, all the better to reveal the music in all its beauty.

Both Pears and Bostridge are excellent with words and their significance. Diction is clear – at times, almost exaggerated with Bostridge, who sings the final consonant of "sick" in the phrase, "O Rose, thou art sick," with such emphasis that one wonders what the Rose did to poor Ian to upset him so! Bostridge also carries the search for meaning one step farther than Pears; not a single word is left unexamined and imprinted in some way. What keeps this from seeming precious, however, is Bostridge's willingness to throw caution to the winds. The words "Sleep no more" at the end of Wordsworth's "But that night when on my bed I lay" are arrestingly shouted out, so much so that listeners inclined to nervousness surely will spill their coffee. It works though – the beauty of Bostridge's singing and his avoidance of anything that smacks of primness make his reading of the Nocturne preferable even to Pears's, heretical as saying so might be. Rattle evokes gorgeous sonorities from his musicians, especially in the obbligato contributions to the Nocturne. Having said that, Britten's conducting was more energetic and forthright than Rattle's. I also don't find Radek Baborák to be nearly as colorful and characterful as Dennis Brain or Barry Tuckwell, who appear on the two Britten/Pears recordings of the Serenade.

The engineering is excellent, and sung texts are included in the booklet. Another attraction of this issue is the interesting and personal booklet note by Bostridge himself.

Copyright © 2005, Raymond Tuttle