The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Gubaidulina Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

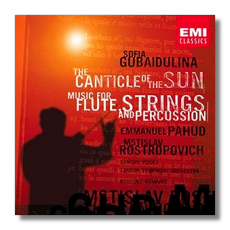

Sofia Gubaidulina

The Canticle of the Sun

- The Canticle of the Sun

- Music for Flute, Strings, and Percussion

Mstislav Rostropovich, cello and percussion

London Voices

London Symphony Orchestra/Mstislav Rostropovich

London Symphony Orchestra/Ryusake Numajiri

EMI Classics 5 57153 2 DDD 75:41

Sofia Gubaidulina (born in the former Soviet Tartar Republic in 1931) has earned immense regard from performers and new music intellectuals for her mingling of sonic innovation with a deep sincerity, and with a respect for the cultural traditions of her homeland. Her music abounds with unfamiliar sounds and equally unfamiliar playing techniques: one of her string quartets has the players bouncing rubber balls off of their instruments' strings. It is impossible, however, to accuse her of innovation for the sake of ego gratification, or merely to shock performers and audiences. Her music, as varied as it is, is consistently personal and honest, and unfailingly humble.

The Canticle of the Sun is based on a text by St. Francis of Assisi. Gubaidulina divides the text – and her work – into four connected sections. The first section glorifies the Creator of the sun and the moon, the second section the Creator of the four elements, the third section life, and the last section death. The scoring is for cello soloist, percussionists, celesta, and chamber choir (six sopranos, altos, tenors, and basses). Gubaidulina, wishing to respect the holiness and simplicity of Francis's words, has tried "to make the choral part very restrained, even secretive, and to put all the expression in the hands of the cellist and percussionists." There are times when the voices come to the forefront, but Gubaidulina treats them mostly in a coloristic and fragmentary fashion. Although there's little about Gubaidulina's music that invites casual listening, its intensity (at every tempo and dynamic level) can't be missed by anyone whose ears are open. The Canticle follows an emotional path that, while steep and difficult to climb, is always clearly marked. The composer's Zen-like sensitivity to each individual sound, as well as to the silences that encircle it, makes the Canticle a work whose drama must be supplied by the listener, as well as by the performer. I find it astonishingly beautiful, and also beautifully strange, just like the saint who inspired it. The dedicatee is Rostropovich.

Rostropovich made his fame as his cellist, of course, and he has had an excellent career as a conductor as well. There are commercial recordings of him as a pianist too (usually accompanying his wife Galina Vishnevskaya). I believe that this is the first time he is credited as a percussionist. In Canticle, the composer asks him to play his instrument percussively (striking it with a drum stick, for example), and then to put it aside in favor of a bass drum and of a flexatone played with a double bass bow, before returning to his cello. "Slava" actually conducts the Music for Flute, Strings, and Percussion, so he plays three different roles on this single CD.

The second piece was written in 1994, three years before the Canticle. Here, Gubaidulina is more overtly dramatic. Forgive my fancy, but Music sounds like a birth-to-death piece to me – its closing moments, which are marked by breath but no tone from the flutist, sound like final exhalations. If Stanley Kubrick hadn't scored the final scenes of 2001: A Space Odyssey with music by Ligeti, Gubaidulina's Music would have worked just as well. It's a long but beautifully paced work – at times frightening, driving, and haunting. Part of its effect comes from Gubaidulina's unusual tuning of the string orchestra: half the players tune a quarter-tone lower. (The composer compares this to "light" and "shadow.") Pahud uses four different flutes – bass, alto, flute, and piccolo – to wrap himself around the music.

These recordings were made in the presence of the composer. I don't see how the performances could be bettered, and who would dare to compete with Rostropovich anyway? Pahud, a much younger musician, already has shown his mettle in the Baroque and Classical repertoires. He is no less impressive in this difficult but rewarding new music. The engineering throughout is excellent. The only thing that left me a little unconvinced was the spotlighting of Pahud at the end of Music; his breaths seemed intrusively loud.

The track information has been severely bungled. The respective timings of 44:39 and 30:42 seem about right, but for Canticle, eleven tracks are promised. Instead, the work ends 8:45 into track 9 – at least I hope it does – and then Music for Flute, Strings, and Percussion starts a few moment later. I hope this will be ironed out on later copies of this CD.

Copyright © 2001, Raymond Tuttle