The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Grieg Reviews

Nielsen Reviews

Sibelius Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

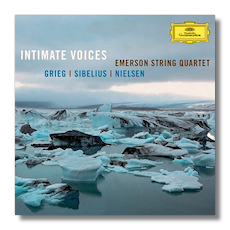

Intimate Voices

- Edvard Grieg: String Quartet in G minor, Op. 27

- Carl Nielsen: At the Bier of a Young Artist, Op. 58

- Jean Sibelius: String Quartet "Voces intimae", Op. 56

Emerson String Quartet

Deutsche Grammophon 4775960 63:41

Summary for the Busy Executive: Sensitive, slightly cool accounts.

From their origins in the English fantasia, string quartets begin in sociable entertainment and end in philosophy and autobiography. Writers usually cite Beethoven as the key to the divide. Even something as striking to our ears as Mozart's "Dissonance" quartet says more about music than about Mozart or about extra-musical ideas.

All three works on this CD's program to some extent indulge in biography, the post-Beethoven side of the divide. None of the composers' reputations depend on these works, although they all wrote, in my opinion, masterpieces (if unusual masterpieces) in the genre.

The Grieg, of course, gets the same lack of respect as most of his large-scale compositions. Even star string quartets who have made wonderful recordings have fought among themselves over whether they should spend time with it at all. As a lad, I first heard the Juilliard in the work and loved it immediately. Of course, I knew nothing about quartet, or even string, writing at the time. I've since found out a few things and can now see flaws, but they don't seem to matter a whole lot to me. The work's passion and melodic beauty reduce such concerns to triviality. Grieg, a pianist rather than a string player, may translate piano writing to string textures, but the results always "sound." The writing is mostly chordal, with just enough contrapuntal leavening to keep interest, although in the finale, Grieg achieves real rhythmic independence for each instrument. Furthermore, Grieg keeps an impressive hold on architecture. A motto-theme – similar to the opening notes of his piano concerto – runs through every movement, with neat rhythmic and modal variations. Obviously, Grieg has conceived the quartet as a whole. The melodic invention is, predictably, abundant and pure genius. The Emerson gives a surprisingly elegant, detailed reading – its very elegance throwing me a curve. "Grieg needs passionate commitment to the beauty of his ideas, rather than to be turned into another Mendelssohn," I thought. After all, the composer had written it in response to a crisis in his marriage, reflected in the sharp alternations from storms to wildflower tenderness. Nevertheless, the Emerson gradually won me over, mainly through superb, intelligent playing.

Nielsen wrote four string quartets around the turn of the century, probably for himself (a violinist) and his friends to play. They are attractive, well-crafted affairs, but certainly without the visionary qualities of the symphonies. The brief At the bier of a young artist, written on the death of a painter friend and played at the funeral, taps an altogether deeper vein of emotion, running the familiar Nielsen dichotomy of chromatic anguish and drop-dead-gorgeous folk-like clarity. In context, it evokes the grief at the loss of a noble life. It's made for the Emerson's cool approach, like Danish Modern furniture. Some accounts push the work into bathos. Emerson gives you the feeling of tragic resignation.

The Sibelius quartet comes from 1909, between the Third and Fourth Symphonies. It stands as his finest, most profound chamber piece, by a lot. That he wrote it under the shadow of death (throat cancer) shouldn't surprise us: it has the air of a testament. What surprises me, however, is how unlike the symphonies it is: no great builds over pedal points, a much more nervous, heavily contrapuntal surface. Of roughly-contemporary quartets, off the top of my head, only the Ravel quartet of 1903, the Schoenberg second (1908), and the Elgar of 1918 achieve at least the same level of distinction. More than many of his works, particularly the Fourth Symphony, Sibelius's idiom acknowledges its foundation in folk melody without actually, like Grieg's, keeping to the general line of folk melody. The muscular first movement, unlike Grieg's, goes for leanness rather than sonority. It begins with solo and ends in unison, moving in the meanwhile along a taut sonata argument, leading directly to a quick quasi-scherzo, based on the same themes. The scherzo comes closest to the allegros of the symphonies, but minus the long builds. It's over in the blink of an eye, but with a powerful effect all out of proportion to its length. The quartet's nickname, "Voces intimae," comes from the adagio third movement, a lament, though again contrapuntal rather than chordal. For a while, scholars thought that the phrase referred to a chamber-music ideal. However, the composer pencilled the phrase over three chords, near the beginning of the movement and so out of key that they interrupt the argument. The effect, at once elegant and striking, has such power that it invites a programmatic interpretation – the brush of a wing from the angel of death, for instance. The composer picks up the argument again, but toward the end, the out-of-key chord reappears, this time integrated into the discourse. Acceptance?

Between the slow movement and the finale, Sibelius inserts a second scherzo, this one in triple time, marked "allegretto (ma pesante)." That somewhat contradictory indication – "pesante" means "heavy" but we usually think of allegrettos as light – provides the key to the movement, heavy and light alternate. The Emerson disappoints here. Its lights are wonderful, but it never gets heavy enough, and thus the contrast never really comes off. The finale begins and ends pretty much in ambiguity. Themes get reduced to accompaniment and supporting figures rise to main interest. It begins fairly conventionally but less than halfway through, it switches directions as it turns into a manic toccata – as the liner notes say, almost two movements in one. The quartet rises to the occasion here, committing to the danger and instability of the movement.

All in all, an attractive program intelligently presented. The one thing I miss from the Emerson is passion, though they certainly provide compensations.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz