The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

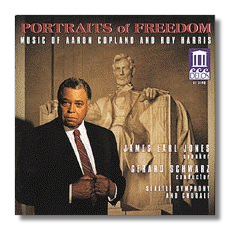

Portraits of Freedom

- Aaron Copland:

- Fanfare for the Common Man

- Lincoln Portrait

- Canticle of Freedom

- An Outdoor Overture

- Roy Harris:

- American Creed

- When Johnny Comes Marching Home

James Earl Jones (speaker)

Seattle Symphony & Chorale/Gerard Schwarz

Delos DE3140

Summary for the Busy Executive: Good Copland; valuable Harris

Another winner in Delos's American series. Of the conductors competing with recordings of American moderns – Schwarz, Thomas, Slatkin, and Knussen – Schwarz has consistently come up with some of the most interesting material. He has heroically revived Hanson, Creston, Piston, Hovhaness, and Diamond and for the most part ignored the current hot American stocks: Copland, Bernstein, Gershwin, Barber. Copland and Bernstein are well-represented on disc by the composers themselves. Consequently, there is a less compelling reason to duplicate than to explore. Even so, Schwarz has given us some out-of-the-way Copland – the Canticle of Freedom and the original brass-and-percussion version of Fanfare for the Common Man.

Last night at a concert, a fellow ticketholder opined that Aaron Copland's music was, believe it or not, "unsophisticated." I think the only piece he had heard was Rodeo, which he associated with middling Westerns and commercials for the U.S. beef council. Even so, I pointed out that he had confused "simple" with "unsophisticated." Fanfare for the Common Man works with simple, even bare, material and manages to say a lot with very few notes. One small indication of Copland's compositional smarts is the fact that the music fits the brass like a Saville Row suit. Furthermore, the piece makes me believe in the Muse. It resembles no other fanfare I know, and the addition of percussion is lagniappe from a genius. The work and the idiom has spawned lots of imitators, none of whom come anywhere close to the incisiveness of Copland's thinking. Copland wrote the piece in response to a World War II commission from the conductor and composer Eugene Goossens, who managed to line up both big names and newcomers. Piston and Thomson contributed fanfares honoring the French. Deems Taylor saluted Russia. Other composers dedicated their fanfares to various branches of the armed forces: Signal Corps (Hanson), "Airmen" (Wagenaar), Medical Corps (Fuleihan), and paratroopers (Creston). Goossens himself honored the Merchant Marine. Only Copland and Morton Gould ("Fanfare for Freedom") took notice of the ideas the war had put at risk. Copland's was the longest and most elaborate work in the series and the only one to have survived its première. Koch, by the way, has recorded Goossens's original series, complete with other modern American fanfares, on CD 3-7012-2, all conducted by Jorge Mester.

I feel the piece has never had a definitive performance, at least in its original version, possibly because it's so spare. First, the conductor must find the right tempo. Performance times of this piece range from Bernstein's zippy two minutes to Schwarz's 3'43". Copland himself comes in at around three minutes. Bernstein and Copland are out because they use the full-orchestra version, derived from Copland's Symphony #3, rather than the brass-and-percussion. Jorge Mester with the original clocks 3'32", and it drags to such an extent, you swear you can see photons moving. Schwarz takes more time and nudges the line of pokey, without stepping over. In general, the performance strikes me as spacious rather than strung out. Part of this probably stems from the fact that Schwarz began as a virtuoso trumpet player – rather than as a pianist, usual for a conductor – and really understands brass technique and sonority. I still want the music to move more than Schwarz drives it, however.

Copland wrote Lincoln Portrait in the 1940s, this time responding to a commission from conductor André Kostelanetz. This was by no means the first symphonic tribute to Lincoln. Gershwin had considered setting the Gettysburg Address shortly before he died. In the 1930s, both Daniel Gregory Mason and Robert Russell Bennett had preceded Copland with Lincoln symphonies, neither of which I've heard. However, a theater acquaintance of Bennett's commented on the symphony that "John Wilkes Booth didn't kill Lincoln. Robert Russell Bennett did." A composer or writer who takes on Lincoln also takes on the burden of Lincoln. The subject – the most eloquent and Romantic American political figure, the great hero of the American national epic of the Civil War – automatically raises our expectations. Copland discussed his plans for the work with colleague Virgil Thomson. A master of setting texts, Thomson advised Copland not to attempt to set Lincoln's words, but Lincoln's words had attracted Copland in the first place. Copland settled on the compromise of a speaker declaiming Lincoln over a musical background (a genre known as melodrama), which, by the way, almost never works. If the music is interesting enough, one resents the words. If the music fails to awaken interest, why have the music at all? Those pieces which do succeed – Walton's Facade, for instance – tend to treat speech as a musical line, with some rhythmic relation to the music itself. Copland came up with inspired music. For the first two movements, the Portrait seems an unequivocal masterpiece – from the "big prairie" opening, to the dance in and around the tune "Camptown Races." Copland has re-imagined American vernacular music and turned it into high modern poetry.

However, these movements are purely instrumental. The problems come in the third, with the addition of the speaker who declaims Lincoln's words as well as a connecting text. Nothing wrong with Lincoln's words, of course, but the connecting text, I assume by Copland himself, is another matter – full of Earl Robinson, knock-off Whitman rhetoric that afflicted much of American poetry during the 30s and 40s. Unless a really fine reader tackles it, it becomes a collection of unintentionally funny non-sequiturs. For example:

Lincoln was a quiet man. Abe Lincoln was a quiet and a melancholy man. But when he spoke of democracy, this is what he said…

and

When standing erect, he was six feet, four inches tall, and this is what he said. He said: "It is the eternal struggle between two principles, Right and Wrong, throughout the world…"

Copland soon recognized the problem, of course. He favored a "flat" reading, as opposed to a flamboyant one. In this, believe it or not, I feel he chose wrongly. I've heard many readers, including Adlai Stevenson and Copland's favorite, Henry Fonda, and they only compound the problem. My favorite reader, believe it or not, was Carl Sandburg (Kostelanetz conducting on a Columbia LP) – corny as hell. I suspect Copland hated it, and I could care less. Sandburg understood instinctively that the connective text was music, pure and simple, rather than a logical argument or even sense, and you listened to a virtuoso declaimer of poetry triumph in a spoken aria. James Earl Jones is my second favorite reader, for the same reasons, although the character of the declamation differs.

Schwarz turns in a fabulous account, full of evidence that he has seriously thought about the piece. Copland builds the work from two motives: a heavy dotted-rhythm slow march and a fanfare idea, similar to the Fanfare for the Common Man. The opening, in which most conductors, including Copland, strive for the epic, Schwarz raises to tragedy. In many ways, it's a nostalgic reading – one that knows more than even Copland at the time of composition could have known. We've lived through Vietnam, after all, and a generation of do-nothing, self-congratulatory politicos. Schwarz starts low, slow, and distant and builds a magnificent span of crescendo. He judges everything so well that the orchestra always has room to get louder. The second movement dances as it should, but a subsidiary theme harmonized in the strings sounds the tragic note again – as if it were the suffering of the disenfranchised under the bustle and optimism of the first half of the 19th century. The third movement is pure magic. Jones takes Lincoln's familiar words out of my school-room (do kids still memorize the Gettysburg Address?) and makes them new. Jones sounds as if he's pondered for himself their significance. He's not simply hitting the rhetorical marks. The album notes point out that Jones, in the famous lines, emphasizes not "of the people, by the people, and for the people," but "of the people, by the people, and for the people" – appropriate to our greatest poet democrat. But it's not all Jones. At the moment where Jones hits "that from these honored dead," a solo trumpet quietly sings the fanfare idea, and the resemblance to "Taps" suddenly hits you – all the war dead, including Lincoln. The portrait of the single sitter has widened to include the uncommon "common men" again.

Canticle of Freedom doesn't get too many performances. On the one hand, it doesn't challenge a crack professional group (Copland wrote it for MIT amateurs). On the other, although finely written, it just doesn't contain enough interesting, vulgar material. I can't point to any single moment that grabs my attention. Copland himself never recorded it, nor did Leonard Bernstein, his greatest interpreter. In short, your life hasn't turned to garbage because you've never heard it. The only recorded competition here is Michael Tilson Thomas leading the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and the Utah Symphony (CBS Masterworks MK 42140). Thomas's account is less subtle and finely-played than Schwarz's and, for that reason, enjoys an advantage. Thomas gives the material the underserved goose it needs. Unfortunately, it's paired with a gruesome choral arrangement and performance of Copland's masterpiece Old American Songs, an homage to the orchestral songs of Mahler. Better here, you should go with Copland and baritone William Warfield (CBS Masterworks MK 42430), an outstanding performance of the stereo era.

Copland also wrote An Outdoor Overture for amateurs – this time for a New York City high school, which gives you some idea of what public-school music programs used to be like. Although the overture lies well within amateur capabilities, a professional orchestra shouldn't be ashamed to tackle it – one of Copland's finest, most energetic works, full of terrific tunes. Howard Hanson once remarked that kids were the toughest to write for, because they knew when you hadn't given your best and didn't tolerate less than that, probably because everything seems possible. At any rate, the high-school orchestra must have had a wonderful time with Copland's overture. Schwarz drags the early trumpet solo terribly, but he's crisp in the quick rhythmic sections. Copland's own reading, less precisely articulated than Schwarz's, still aces out the rest of the competition, simply because he recognizes the piece is fun, damnit.

At one point, many thought of Roy Harris as our first great native composer. Koussevitzky called Harris's Third Symphony the finest by an American, and the conductor had certainly heard (and commissioned) a great many American symphonies. Funny how these things work out. When Koussevitzky died, noone stepped forward to champion Harris. Bernstein continued to program the Harris Third, but he never explored Harris as he did Copland and Stravinsky. For years, I read unflattering things about Harris, mainly centering around a comically-outsized ego. Harris became an uncomprehending punchline to a joke. I finally heard Abravanel's performance of the Symphony #4 "Folk-Song," and while an uneven work, it showed me an undeniably interesting musical mind fashioning a very sophisticated idiom from folk tunes, different from either Copland or Thomson. I then started grabbing all the Harris I could find. It taught me two lessons I should have learned by then: always listen to the work for yourself and even a flawed human being can write marvelous music.

American Creed falls into two parts: "Free to Dream" and "Free to Build." The titles lead one to suspect a programmatic work, but I find both parts more abstract. They set a large emotional frame for the music, but closer looks for more specific links I believe would not pay off. Harris has an idiosyncratic sense of melody, counterpoint, and harmony. You can't often point to definite themes. Harris essentially takes a melody for a walk, constantly changing the shape of seminal ideas and the new ideas thus created in turn sparking new material for variation. I've met with only one other composer who deals in this process – Allan Pettersson – and he inhabits a far bleaker world than Harris. Another Harris trait is the enharmonic, or common-tone, modulation, usually on the third of a chord. For example, a C-major chord (C-E-G) might change to an E-major chord (E-G#-B, with E the common tone) or to an A-major one (A-C#-E). Normally, composers pull off this kind of stunt with music that moves like a hymn – all voices moving together. Harris does it contrapuntally, through the confluence of independently-moving voices. The effect is of a music constantly "becoming," sort of like Faust in the final scene of Goethe's poem. However, the sensibility is – as the critic Herbert Elwell pointed out – "one hundred percent American." There's a striving, muscular optimism to much of Harris's work (think of the fugal theme in the Symphony #3), but he's hardly a jingo. Whatever Big Moments Harris gets are earned, usually the result of a long musical meditation. The pensive side of his music kind of reminds me a bit of the statue in the Lincoln Memorial – at once visionary and tender. American Creed forsakes tub-thumping for that kind of thought. To some extent, the spare opening of "Free to Build" may momentarily remind a listener of the quieter moments of Copland's Appalachian Spring, but it turns into something else, as soon as the thought flits across. For Copland, the spareness is the emotional point. For Harris, it's merely the beginning of the exploration. An American, I react to Harris's music the way I imagine an Englishman reacts to Elgar or Vaughan Williams – that is, at a level absolutely irrelevant to the technical merits of the piece, considerable though they might be. In Harris's case, considerable indeed. "Free to Build," for example, is a triple fugue. Yet even here, the fugue is merely a means. Harris constructs a sound-world I can imagine Lincoln and Whitman in – that is, the best of my country.

When Johnny Comes Marching Home doesn't quite belong in the same league, but it's not nothing either. It stands in the same relation to Harris's best as Vaughan Williams' Sea Songs does to, say, the symphonies. It may prove instructive to compare this work with Morton Gould's American Salute, based on the same tune. Where Gould constructs a set of brilliant variations loosely stitched together, Harris really goes for another symphonic movement. He chops the tune up, plays with it, finds other related ideas and plays with them as well. It doesn't quite come off, despite effective sections, possibly because the tune's strong profile resists that kind of treatment.

Kudos to Gerard Schwarz for, if nothing else, the programming. I'm not aware of a previous recording of American Creed, which strikes me as one of Harris's best and eminently sinkable by a bad performance. Schwarz's account is advocacy of a highly persuasive order. Auden once wrote, "Some books are undeservedly forgotten; none are undeservedly remembered." Thanks to Schwarz, I can remember this piece.

Some of my pleasure in records and discs derives from the liner notes as well as the music. Much of my musical education I received from the back of album covers, and I make no apology for it. The liner notes here struck me as unusually knowledgeable and elegantly written. I cheated and flipped the pages ahead to the byline – Paul Moor, for many years Musical America's man on the spot in Germany. Someone once described Moor as "the man who met God in the dressing room" – well, at least Stravinsky, which to me comes close enough. Moor certainly has been in the thick of modern American music (New York branch) while it was happening. Various authoritative biographies have relied on him. All this lends an immediacy to the notes, which give you solid information as well as the testimony of the fellow who was there. Pure lagniappe.

Copyright © 1997, Steve Schwartz