The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Mussorgsky Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

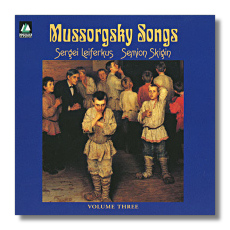

Modest Mussorgsky

Songs - Volume III

- Gde ty, zvyozdochka? (Where are you little star?)

- Vesyoly chas (The hour of jollity)

- List'ya shumeli unylo (Sadly rustled the leaves)

- Mnogo yest'u menya teremov i dadov (I have many palaces and gardens)

- Molitva

- Otchevo, skazhi, dusha-devitsa? (Tell me why)

- Shto vam slova lyubvi? (What are words of love to you?)

- Duyut vetry, vetry buynyye (The wild winds blow)

- No yesli-by s toboyu ya vstretit'sa mogla

- Malyutka (Dear one, why are your eeyes sometimes so cold)

- Pesn startsa (Song of the old man)

- Tsar Saul (King Saul)

- Noch (Night)

- Kalistratushka (calistratus)

- Otverzhennaya (The outcast)

- Kolybel'naya pesnya (Lullaby)

- Pesn baleartsa (Balearic Song)

Sergei Leiferkus, baritone

Semion Skigin, piano

Conifer 75605-51265-2

Let's face it. When we think of classical songwriters, we think of Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, and possibly Hugo Wolf. These names dominate most song recitals and recordings. We have focussed our attention on the riches of the German Romantic repertory to the exclusion of just about everybody else. I can't remember the last time I heard a Fauré song in concert, and to me, Gabriel Fauré is at least as great a master of songs as Wolf. The French song has become largely the purview of "specialists" (people who can pronounce French). Fauré to me is France's greatest, but what a second string! Claude Debussy, Henri Duparc, Reynaldo Hahn, Maurice Ravel, and Francis Poulenc - they get slighted as well.

I think the neglect due mainly to language difficulties. Schooled singers are taught mainly Italian and German, on the hope that they will work in opera, a field dominated by Italians, Mozart, Wagner, and Richard Strauss. As a result, most native English speakers (including some currently big names) sing classical songs in their own language with great awkwardness. With Russian songs, you actually have to learn a whole new alphabet, as well as a panoply of new vowels, consonants, and stress patterns. Consequently, most great exponents of Russian songs have been native Russians or native Slavophones. However, a singer willing to work can uncover masterpieces by Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Glinka, Tchaikovsky, and Borodin. Tchaikovsky, a composer popular in the west, wrote a ton of songs that you hear about as often as you see a St. Bernard dressed like Carmen Miranda.

Of the Romantic Russian song writers, I find Mussorgsky the greatest in dramatic and emotional range, as well as in the variety of song types. Borodin may give you yummier, more seductive melodies and Rimsky produce gems of melody and accompaniment that fit together like the click of the lid on a well-made box, but Mussorgsky knocks you off your pins. It's kind of the difference between the refinement and sensuality of a Monet on the one hand, and the near-brutality of a Cezanne on the other. Mussorgsky wrote three masterful cycles: the macabre and powerful Songs and Dances of Death, the introspective Sunless, and The Nursery, the last an astounding example of an adult thinking himself successfully into the mind of a child. None of the output of any of his contemporaries comes close to these songs' artistic reach and psychological insight.

The great Bulgarian bass Boris Christoff traversed the "complete" songs (or what was known at the time) in the 1950s, and it remains a splendid monument of recorded music (EMI CMS 7 63025 2, mono). I first discovered it in my college library during the Sixties, and it opened up the entire Russian song literature. Since then, Russian songs have mainly been bones thrown in on singers' recital albums or motley collections. Furthermore, Mussorgsky has suffered (and at times benefitted) from his editors. Kim Borg, for example, did the Songs and Dances of Death for Supraphon in bloody awful, mercifully uncredited orchestrations, and I find him way too stiff, besides. The American George London released a very fine version indeed on the old Columbia label, but his voice takes some getting used to. At one time, it reminded me of what Donald Duck might have sounded like, had he forsaken cartoons for classical music and become a baritone. I've since accepted it. Oda Slobodskaya came out with at least two albums of Russian songs for the Saga label in Britain, but her voice wobbled, in classic Russian diva fashion, so widely that you couldn't tell within a half-step what pitch she thought she hit.

It's about time someone went back over Christoff's ground. Christoff also resorted to orchestrations for some of the songs, mostly by Rimsky, Glazunov, and (I suspect) his main accompanist for the project, Alexandre Labinsky. The orchestrations are first-rate, but it's nice to hear what Mussorgsky actually wrote. Christoff was, of course, one of the great Boris Godunovs - for once, a true bass in the role, rather than a bass-baritone. His dramatic style was big, like Chaliapin's, on whom he had modeled himself. I find him powerful in these works, but some may consider him hammy. To me, the songs can take it. The young Russian Sergei Leiferkus has a more refined style, but a lighter, brighter voice. This CD is, of course, the third volume of a series. I have not heard the others, and, very likely, Mussorgsky's greatest work comes from the earlier volumes. Mussorgsky wrote most of the songs here early. The "Balearic Song" from the opera sketch Salammbo is here, for instance. The rest are all fugitive pieces.

The hard, musical task posed by Mussorgsky's songs is finding the pitch. As you might expect, the melodies do not travel well-worn paths. In some, odd leaps from one note to the next abound. In others, like Sunless, Mussorgsky forges his own chromatic style, probably derivable from Liszt, but sounding like nobody but Mussorgsky. Music this harmonically unstable doesn't come again until Schoenberg. Leiferkus has all this stuff licked. Furthermore, he produces an outstanding legato line. You can barely tell when he takes a breath, something you really can't say of Christoff. Christoff has a bigger, richer voice and sings on a grander scale, but he's also got the bigger wobble. Leiferkus treats the songs as "extreme Lieder." Dynamics and sound are held back, but - and this is important - the singer delivers just as great an emotional punch.

Recorded sound is superb. Skigin supports his singer admirably. I still find the Christoff viable. If you must have stereo sound or you prefer a more Lieder -like approach, then Leiferkus is the way to go.

Copyright © 1997, Steve Schwartz