The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Arnold Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

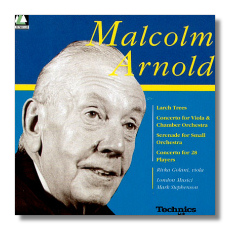

Malcolm Arnold

- Serenade for Small Orchestra, Op. 26

- Larch Trees, Op. 3

- Concerto for Viola and Chamber Orchestra, Op. 108

- Concerto for 28 Players, Op. 105

London Musici/Mark Stephenson

Rivka Golani, viola

Conifer Classics 75605-51211-2

I have no idea what "real composers" think of Malcolm Arnold, and I'm not sure I really care. Those whose spines stiffen with high principle are welcome to sniff. For myself, I don't see how anyone with the slightest interest in orchestral sound can dismiss his work, even the opus 1, Beckus the Dandipratt Overture, astonishingly mature, full of Arnoldian fingerprints. However, although he seems to have hit on the right road right away, he does wander a bit early on.

Larch Trees, Op. 3, essays Delian nature painting, but it stands at odds with Arnold's musical bent. Unlike Delius, whose orchestration often sounds on the heavily lush side, favoring lots of doubling, Arnold takes the usual modern approach of keeping the individual voices of instruments distinct. Even when he assigns a line to an instrumental ensemble, he rarely produces an homogenous sound. He is less interested in the ambiguities among instrumental combinations than in their contrast. Larch Trees is mostly pretty bare. Often the instrumental texture reduces to one or two instruments. It's an interesting piece, but mostly in the light of Arnold's later work.

With the Serenade for Small Orchestra, we move into familiar Arnoldian territory. The opening sounds, with a minimum of instruments, ravish me. The movements are short but concentrated, like a haiku. The second movement features a tender solo for flute, with a hint of blues inflection. This isn't Arnold's later clash of high and low idiom, but a sublimation of jazz into a personal musical poetry. In a way, the second movement shows a surprising intensity, given the natures of the first and last movements. This often happens in Arnold. Something dirt-simple plunges suddenly into the deep, as in the opening movement of the Second Symphony. The finale works the Walton high-spirits game, although without Walton's emphasis on fizzy counterpoint. All in all, a charming and beautifully-worked piece.

The late Christopher Palmer, in his very odd liner notes for the CD, refers to Arnold attacking compositional problems "as if they didn't exist," in his remarks on the Viola Concerto. By this he means, of course, the difficulty (mostly having to do with the instrument's range) of getting the solo viola to sound through the orchestra. Given Arnold's penchant for creating distinct planes of sound (as opposed to an aural sea) with his orchestra and his normally economical use of instruments, the problem really doesn't come up in his style. This is not a Big Bow-wow concerto, in any case; few of his concerti are. The opening movement is the usual Arnoldian no-fuss neoclassicism, tinged with a bit of nostalgia in the second thematic group. The second movement again surprises with its depth – a stark, almost single-minded meditation on the viola's introverted opening solo. The finale yanks us out of melancholy with a genial combination jig-and-foxtrot alternating with aggressive, insistent punctuations from orchestra and viola.

For me, the most interesting work on the CD is the Concerto for 28 Players, because Arnold – like Berg in the Chamber Concerto and Strauss in Metamorphosen – means exactly what he says. Each player gets a chance in the spotlight with virtuoso writing, then steps back to let someone else come forward. It's Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra taken one step further. Only a master planner can bring off something like this. Arnold responds with vigorous, heartfelt music that makes you forget the planning. A marvelous piece.

Mark Stephenson and his players have done a wonderful job for Conifer's Arnold series, concentrating on the smaller works and shining light on some of the obscure places in the composer's catalogue. The performances are clean and rhythmically alive. The sound is better than concert-hall real, but not hokey.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz