The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Vasks Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

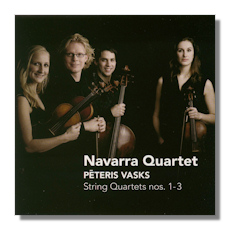

Pēteris Vasks

String Quartets

- Quartet for Strings #1

- Quartet for Strings #2 "Summer Tunes"

- Quartet for Strings #3

Navarra Quartet

Challenge Classics CC72365

"I have always dreamed that my music would be heard in the places where unhappy people are gathered," wrote Latvian composer Pēteris Vasks, who was born in 1946. But unhappy for which reasons: personal or national? Or doesn't it matter? Isn't the greater skill of the composer to distill the emotion into music in such a way that those unhappy in love and/or because of oppression and so on can all relate to the feeling? That's what Vasks seems to be so good at. Admittedly, Vasks is inevitably aware of the suffering of the Latvian people at the hands of totalitarian Soviet government. But – as he has also written – he is at pains (literally!) to identify with all those who suffer, have ever suffered and can appreciate the suffering of others. Although one wouldn't want to overplay the role of melancholy in Vasks' work, for much of it aspires to harmonies and tonalities of great abstract beauty as well, it needs only a bar or two's listening to sense a composer who is actively engaged upon some kind of reconstruction of what life has attempted to destroy.

Vasks' is not a heroic defiance, like that of Beethoven, or Shostakovich. Nor a despair, like Mahler's, Tchaikovsky's or Schubert's. Still less does he repeat variations on external melancholy ideas, or preach tears. Like some of Schnittke's bleakest moments, Vasks leaves you with the impression that there is – at least as long as the mood lasts – no real alternative to the depressed, slow and thoughtful sound world which he inhabits. Now here is the first recording of the composer's first three string quartets (he has so far written five). The music serves not to re-inforce the composer's convictions about sadness by strumming on the same note or theme. Nor, really, even to explore unhappiness in another medium. Rather he's intent on exploring the music in its own right, while not exactly pushing its limits. Nevertheless, he brings something distinct and pleasing to it, as did, say, Britten in his three string quartets or even – again – Shostakovich… music a little apart and to be protected. Certainly, much of the music on this generous CD at over an hour and a quarter, is slow and thoughtful; for all their intimacy, the three quartets are expansive and expressive. Vasks's is not, though, an exercise in unadulterated melancholy and derision of hope. Ultimately, the music should be seen to provide its own (cause for) hope.

The three string quartets (from 1977, though revised 20 years later; 1984, and 1995) are presented here in reverse order. A common theme, common sound, is that of birdsong – but neither as conceived by Messiaen nor Rautavaara. The calls, impressions, flurries (you can almost taste the feathers a minute into the first quartet's first movement's "Intrada" [tr.8]!) and mournful comments are there as representative of the stability of nature – as are wind and cold, or warmth and light. The second quartet, indeed, is subtitled "Summer Tunes" (Sommer Gesänger) and provides a modicum of relief from, and contrast with, the dourness and heartrending tone of the rest of the music.

Tempi vary greatly in these works. They are no minimalist constructions with long, slow barely shifting harmonic walls. The third quartet's second movement, for example [tr.9], has excited, breathless, almost childlike tergiversations as well as almost languorous dips, and then again staccato semi-quotes of Beethoven and menacing motifs in the cello and lower viola strings. Nor is this color for color's sake. It bespeaks the kind of manic thrashing around that those facing the worst are compelled to try, and to try and avoid. Repeated listenings to Vasks' string quartets reveal a surely intentional yet largely unarticulated challenge on the composer's part that defies you to become comfortable in any kind of familiarity with the music. This is not because it's spiky, disjointed or overtly atonal. But because each episode of raw emotion never quite dissipates before the next arrives, or is recalled.

The Navarra Quartet was formed as recently as 2002 at the Royal Northern College of Music in the UK. Within as few as five years they had already won several major awards. It's not hard to see why: their playing is not only temperamentally well suited to Vasks' music, can easily encompass the range of techniques he calls for (extremely quiet, animated, almost microtonal sul ponticello, glissandi, accentuated portamenti, searing crescendi and so on); but it's also playing that's able ‐ by sheer virtuosity alone – to convey in a couple of bars Vasks' precise intensions of pitch, rhythm and ensemble. Theirs is a wholly idiomatic, undemonstrative yet persuasive approach to Vasks. Most importantly, perhaps, they seem to have captured (for it's at times elusive) understood, internalized then almost effortlessly expressed that delicate balance that the composer creates between private and public suffering. If Vasks had used words instead of notes, this relationship would be crass; as it is it's poignancy personified

The acoustic is very close, almost claustrophobic. It's a studio recording in Leipzig which aids the sense of intensity. The liner notes are eloquent and give much useful background. No-one who loves Vasks music should neglect this CD. Lovers of (twentieth century) chamber music will otherwise find much to please. And anyone wanting the stimulus of music that's very aware of a variety of human emotions and is played exquisitely and with great technical deftness is likely to be moved and want to listen many times. Recommended.

Copyright © 2011, Mark Sealey.