The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Schumann Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

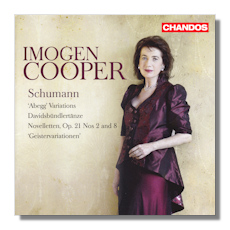

Robert Schumann

- Abegg Variations, Op. 1

- Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6

- Novelletten, Op. 21 #2, 8

- Geistervariationen, WoO F39

Imogen Cooper, piano

Chandos CHAN10874

English pianist, Imogen Cooper (born in 1949), is one of the most respected, articulate and persuasive exponents – chiefly of the Classical repertoire – performing today. Her CDs of Mozart and Schubert in particular always command attention and prove distinctive and of lasting appeal. Here from Chandos is her first all-Schumann CD with numbers 2 and 8 of the Novelletten, Op. 21; both books of the DavidsBündlertänze, Op. 6, in the revised edition of 1850; the "Abegg Variations", Op. 1; and the much less often-heard "Variationen über ein eigenes Thema", WoO, F39 (the Geistervariationen) from 1854; all in a generous hour and a quarter's focused, expressive and highly satisfying collection.

Cooper, the daughter of musicologist Martin Cooper, was born and grew up in London, where she studied with Kathleen Long; then in Paris with Jacques Février and Yvonne Lefébure, and in Vienna with Alfred Brendel, Jörg Demus and Paul Badura-Skoda. It's tempting to argue that her playing easily and evidently reflects the amalgam of these giants of the last century. Its intangibly apposite combination of sensitivity, insight and confidence owes much to their styles.

But there is sufficient difference between, say, a Badura-Skoda and a Brendel. It quickly to become obvious that each of these three qualities (particularly her confidence and the originality which she brings to every bar of the music she chooses to play) is her own in every way. Like her teachers, her extensive experience in Lieder with, particularly, baritone Wolfgang Holzmair contributes significantly to an understanding of Romantic lyricism and Classical restraint.

All these qualities (and many more) are evident in abundance from first note to last on this wonderful recital. Schumann's understanding of tonality draws the listener into a secure and compelling world in ways not used by composers before – particularly his command of effective modulation across and towards moods, as well as to hint at their color as much as explicitly to expose sensation. Just as Cooper's playing of Mozart succeeds because it never unduly emphasizes effect or affect, and of Schubert because it uses his wistfulness, melancholy and pathos as starting points to illustrate more universal musical truths, so she achieves her success with Schumann by never relaxing into over-sentimentality; while at the same time not once suggesting rush.

This is particularly noticeable when considering the tempi at which Cooper plays each of the pieces here. She employs Goethe's maxim, "Ohne Hast, doch ohne Ruh" ("Not in haste, nor yet at rest"). The pace is focused; it acknowledges momentum and purpose; yet it's aware of every foot of the landscape through which her almost brisk walk takes us. A good example of this is the contrast which she brings to movements like the "Zart und Singend" ("tender, or delicate, and cantabile") movement of the DavidsBündlertänze [tr.15].

Cooper almost imperceptibly reveals such contrasts, though. She does not use them for effect or merit – because cantabile need not always imply delicacy or the fondness associated with tenderness. She sets up tensions through such relief, through her sense of variance, contrast. This juxtaposition of tone and time invite us to see not only both antipodes, but also the shades in between. This is particularly appropriate in such a Schuman movement as this "Zart und Singend" once, where a dialectic is to the fore. It's the dialectic, of course, between the impetuous and the lyrical or poetic sides of the composer's temperament in the persons of Florestan and Eusebius respectively.

At the same time, it would be false, unnecessary and certainly counter-productive for Cooper to have forced differences and oppositions (where they do not exist). Rather, she is really working with Schumann's genius in exploiting the way in which we remember his complex construction of humor, atmosphere and temperament. Her great skill seems to begin with an overall grasp of what the music is designed to achieve; then to separate which elements may be considered conscious on the composer's part, and speculate on which aspects must emerge unconsciously (repetition, unexpected passing passages, for instance); and only then to see playing the notes as the means (for her) to communicate this whole to the listener. For Cooper is a consummate communicator. She clearly wraps herself in the music as she's playing it; but it's always played for us to listen to.

There are times, very few of them, when Cooper's gentle enthusiasm for the music may come across as a kind of unevenness, a slightly noticeable living in the moment, rather than an interpretation that's the result of a lofty, more detached overview. This can best be sensed, perhaps, in the first three "Abegg" variations [tr.s 21-24]. Yet for each of these moments of exuberant near over-involvement, the pianist's controlled spirituality touches us surely as Schumann would have wished. This can heard well in the "Theme" of the F39 variations, to be played "Leise, Innig" (quietly, heartfelt) [tr.27], for example. It is inner awareness as much as it is notes on the piano. And when it returns to end the CD, it's understated, quizzical, inconclusive, almost – in a way that sums up the 75 minutes of beautiful playing in which we've been immersed without really being aware of time passing.

Her skills at this projection are never greater, perhaps, than in the second of the two "Novelletten", Op. 21, Number 2 [tr.20]. It's the shorter of the two presented here; the pieces represent the most extended movements on the CD, though. Yet Cooper's totally-assimilated sense of compactness paradoxically allows her to expand in caressing (never coaxing) flavor, color and nuance out of the music – in the way she'd famed for doing in Mozart, and Schubert in particular. No lingering, no sentimentality or mawkishness. Yet a complete sense of emotion, reflection and self-awareness. This is achieved too through that steadiness of performance that can only come through a total and intimate knowledge of every single note, every marking, every possible variation in timing and phrasing. Then the result is that we feel we are in as strong a pair of hands (and a heart and a brain). The very match for a Brendel or Demus.

The recordings were all made on a Steinway in the Concert Hall, Snape Maltings, in November 2014, which is one of the world's (certainly the UK's) most felicitous acoustics. Cooper's every nuance and dynamic are revealed throughout the entirety of each of these nearly three dozen tracks. But they are nicely "set" in a controlled resonance such as to suggest the grandeur and scale of Schumann's achievement in the at times symphonic idiom, when the medium of the piano is so close and personal… the opening of the fifth "Einfach" movement of the DavidsBündlertänze [tr.6], for example. Essays by Nicholas Marston and a note by Cooper herself illuminate these works in the same way as do the performances. They are not to be missed no matter how many other recordings of these works you may have. Warmly recommended.

Copyright © 2015, Mark Sealey