The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Bainton Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

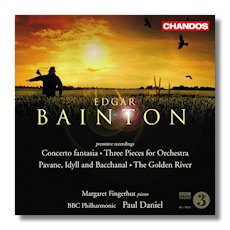

Edgar Bainton

Orchestral Music premières

- 3 Pieces for Orchestra (1920)

- Pavane, Idyll and Bacchanal (1924)

- The Golden River, Op. 16 (1912)

- Concerto fantasia (1920)

Margaret Fingerhut, piano

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra/Paul Daniel

Chandos CHAN10460 68:35

Summary for the Busy Executive: E. Bainton, Gent.

Edgar Bainton (1880-1956) studied with Stanford and had his first successes early in the century. Thus, although younger than Vaughan Williams and Holst, he belongs to that generation we generally describe as the first wave of the English Musical Renaissance. Despite all the horror stories you hear of Stanford as a teacher, all of his successful students came away from him with at least a first-class composing technique. Bainton's own gift was relatively small, however. He tended to accept the music around him, rather than to explore – as even John Ireland did – new ways of making it. In a sense, he was the perfect academic (which he became both in England and in Australia) – not that his music was itself pedantic, but that it was both so assured and so conventional.

The Golden River, based on a tale by Ruskin, is a case in point. It's very well-made – beautiful, poetic orchestration, a confident handling of form – but it's small, even for its fairy-tale genre. It doesn't make a lot of ripples as a similar group of miniatures like Holst's Suite #2 for Band or Vaughan Williams' Wasps does, let alone Ravel's Ma mere l' Oye, all earlier or roughly contemporary. Indeed, the first movement, which depicts storm and destruction, could have been written by Stanford himself, and twenty years earlier, to boot.

The 3 Pieces show a tentative stretching and have an interesting history. Bainton travelled to Bayreuth in 1914 and found himself behind enemy lines when war was declared. The Germans interred him and made him music director of the camp. In addition to founding a madrigal group and several chamber ensembles, he provided incidental music for camp productions of the Shakespeare comedies Twelfth Night and The Merry Wives of Windsor. After the war, he revised the score for orchestra. The works strike a more decidedly English tone, though still not as strongly as Bainton's folk-based contemporaries. More importantly, they reveal a solid lyric gift. The first movement, "Elegy," is my favorite of the three, originally meant to accompany Viola's lament for her twin, Sebastian, in the first scene of Twelfth Night. It captures both her sadness and her enchantment with the country on whose shores she has washed up. "Intermezzo" describes Windsor Forest from Merry Wives, while the final "Humoresque" is a genteel cameo of Sir John Falstaff.

Pavane, Idyll, and Bacchanal, the latest piece on the disc, takes the most harmonically adventurous risks, although those risks had been taken at least fifteen years before by Holst. I compliment the Pavane by calling it Elgarian. It has the piquancy of some the numbers in Wand of Youth as well as beautiful scoring. The Idyll, with prominence given to a solo flute, operates at a slightly lower level, not quite reaching the magic of the Pavane. The Bacchanal, in 5/4 time, shows Bainton cutting loose as far as he can do so. As I said, Holst already travelled this ground, and with deeper tread, but it's still a lovely miniature.

Bainton got the idea for the Concerto fantasia in 1909, when he heard Busoni play the Liszt first piano concerto as well as his own monumental piano concerto. He began sketches in 1917, while still a German internee and finished the work in 1920. It's the most ambitious piece of his I've heard. It owes an obvious debt to Liszt, if not to Busoni, but it's beautifully and thoughtfully worked. The Liszt concerto features two cadenzas in its first movement and varies two main ideas for its entire length. The cadenza idea appealed to Bainton, and he made it the foundation of his structure. This led him to tack the "fantasia" label onto his concerto. "Fantasia," however, implies something loose and disorganized, whereas Bainton lays the fundamental architecture of the entire score in his cadenza, like Liszt, burying the concerto's ideas concerto in the opening "quasi fantasia" section. Bainton works at an extremely basic level. The main idea of the concerto consists of the melodic implications of a harmony rather than a set of specific themes, as well as of melodies that emphasize the major or minor sixth degree of the scale (A or A-flat in the key of C). Bainton's a lot more subtle than Liszt, and the concerto moves with near-Elgarian fluidity of thought. I hope there are more Bainton scores like this one.

Paul Daniel, who has led some wonderful Vaughan Williams and Walton, takes the helm here, always representing the composer well and occasionally making magic. Still young, he has room to grow, and I hope he does. Margaret Fingerhut tackles the Concerto fantasia, straightening out its Lisztian twists and turns with deep musicality. I suspect her tone isn't all that big, but Daniel and the engineers are considerate. A lovely

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz.