The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Vaughan Williams Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

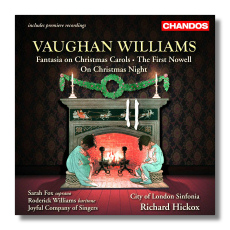

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Christmas Music

- Fantasia on Christmas Carols

- On Christmas Night

- The First Nowell

Sarah Fox, soprano

Roderick Williams, baritone

Joyful Company of Singers

City of London Sinfonia/Richard Hickox

Chandos CHAN10385 69:36

Summary for the Busy Executive: Lovely and lovingly done.

According to Bertrand Russell, Vaughan Williams at Cambridge was "the most frightful atheist." Later, he settled down to become, according to one of his friends, "a cheerful Christian agnostic." Even his superficially religious music falls into the categories of the literary, the utilitarian, or the composition feat, rather than an expression of spiritual need. Michael Kennedy observed that music probably was his religion – that is, whatever glimpses of the super-mundane the composer got came primarily through music and, I would add, secondarily literature and painting. As his oratorio Sancta Civitas shows, Vaughan Williams knew his Plato (in the original Greek) as well as he knew his Bible.

However, Vaughan Williams consciously set out to become an English Composer, to write (in the words of Debussy) music "sans Sauerkraut," or bouillabaisse, for that matter. At the same time, he knew very deeply the traditions and latest trends of music on the continent and took what he could. Nevertheless, he drew his main inspiration from the English past, which included folksong, folk dance, the Tudor composers as well as Parry and Elgar, the long, strong tradition of secular English literature, and of course religious art, like hymns and religious poetry. Christmas, especially the Christmas carol, attracted him in his childhood and lasted throughout his life. The music on this disc, for example, spans over four decades.

The Fantasia on Christmas Carols comes from 1912, two years after the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. Like the latter work, the title misleads you about the nature of the score. Neither work rambles like a fantasy, but instead coheres with symphonic logic – Tallis more than the later piece. Vaughan Williams may sound as if he's just singing one carol after another, but he hides considerable motific art in the orchestra. However, he uses only two carols that come anywhere close to general familiarity: "The First Noël" and "On Christmas Night." I had known a lot of carols before I heard this piece and had never previously encountered the main ones heard here. Furthermore, "The First Noël" belongs exclusively to the orchestra, and then only in fragments. The score begins with a haunting solo cello passage which leads to baritone soloist and choir singing "The Truth sent from above." The choir then launches into "Come all you worthy gentlemen" (which sounds to me like a variant of "God rest ye merry, gentlemen"), followed by the baritone soloist and choir trading phrases of the Sussex Carol and a conclusion of contrapuntal fire as carols and fragments bubble up and recede in orchestra and choir. A long softening begins, and the Fantasia ends quietly with the baritone and choir gently wishing us a happy new year. The overall effect lies as far away from "Jingle Bell Rock" and "Rudolf, the Red-Nosed Rangifer" as one can get. It takes us to a place beyond the commercial noise and glitz of the season. One needn't be a Christian to love this work, for it celebrates warm-heartedness and charity above all.

On Christmas Night (1926) is absolutely new to me. Michael Kennedy's standard book on the composer's life and works doesn't mention it, except in the catalogue. This is its very first recording. Vaughan Williams called it a "masque," mainly because he hated the ballet's dancing on point, and he appropriated Dickens's "Christmas Carol" as its basis. He also drastically telescoped Dickens's plot. It's Vaughan Williams light, but "light" doesn't mean "slight." One hears many pointers to such works as the Seventh Symphony and Pilgrim's Progress. It begins with "God rest you merry" and ends with "The First Noël." Scrooge shuts out the carolers who sing "tidings of comfort and joy." A ghost (only one) shows up and takes Scrooge to Christmases past and present. Scrooge is repentant but hesitant. Tiny Tim leads him to share the family circle as the choir "all with one accord" sings "The First Noël." Vaughan Williams had known both carols since childhood, and they apparently dug their way deep into him. "The First Noël" indeed may have counted as his favorite carol. Although not as powerful as Job or as mystical as the Fifth Symphony, On Christmas Night still contains delightful nuggets. I'm particularly fond of the set of dances at Fezziwig's Christmas party.

The First Nowell comes from the year Vaughan Williams died, 1958. In fact, he died before he could finish it. His amanuensis, Roy Douglas, completed the work (about a third of it needed to be orchestrated and fleshed out from sketches). After World War II, several ugly rumors arose that Douglas had done all the orchestrations of the composer's recent works. Vaughan Williams responded, in his self-deprecating humorous way, that it wasn't fair to attribute the scoring to Douglas, since Douglas was a professional musician who made his living by, among other things, orchestration. Now that Vaughan Williams was gone and could no longer defend himself, Douglas insisted that Oxford University Press (the composer's publisher) indicate through the initials "R. D." those sections that Douglas had worked on, since he didn't want VW "to be blamed for my shortcomings." I've actually seen the score to The First Nowell but can no longer remember who did what. I believe that's probably a measure of Douglas's success.

Don't expect another Hodie. Much less ambitious, the work consists essentially of music for a Nativity play, adapted from medieval pageants by Simona Pakenham. Pakenham initially wavered about going to Vaughan Williams, since she knew he was in the middle of several large works (including another opera – unfinished, of course). She decided he couldn't do anything worse than turn her down and so explained the project to him: the Christmas story, from Annunciation to Nativity, told mainly through carols. Vaughan Williams immediately took to the idea. Perhaps remembering On Christmas Night of about thirty years before, he also remarked to Pakenham, "I think that every Christmas play ought to begin with God rest you Merry and end with The First Nowell." And, after a short prelude, so this score does. It also uses nine more carols: "God rest you merry," "The Truth sent from above," the medieval "Angelus ad virginem" and "Nowell, Nowell, Nowell, this is the salutation of the angel Gabriel," two versions of "The Cherry Tree Carol," "As Joseph was a-walking," "A virgin most pure," "The Sussex Carol," and "How brightly shone the morning star" in VW's English translation. The settings are mostly straightforward. "The Truth sent from above" is nearly identical to its older brother in the Fantasia and, because of that, seems to me the weakest. It would have sparked greater interest to hear another take from the composer on this carol. Had he lived, perhaps he would have revised it more thoroughly.

The main attractions of the score lay in the choice of carols, where the obscure mix with the familiar, and of course in Vaughan Williams's settings, designed to maintain the integrity of each tune. My favorite section is the march of the three kings, based on the chorale "Wie schoen leuchtet der Morgenstern." While less elaborate than the corresponding section of Hodie, it elicits the same general response from the composer and becomes an occasion to show what he can do with large forces.

The late Richard Hickox leads a beautiful performance of all three works. Indeed, his Fantasia on Christmas Carols I think the best I've heard. Sarah Fox is sweet-voiced in both On Christmas Night and The First Nowell. Roderick Williams (or maybe Simon Keenlyside) may well be my favorite baritone right now. He possesses a beautiful voice which he uses intelligently. His breath control seems to know no limit and allows him to phrase anywhere he wants and to subtly color his line. The choir and orchestra are thoroughly professional, but it's the ensemble and the music that become the stars. Highly recommended.

Copyright © 2010, Steve Schwartz.