The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Vaughan Williams Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

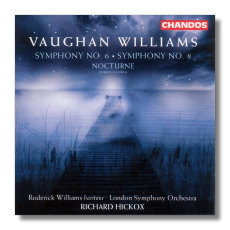

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Symphonies

- Symphony #6 in E minor

- Symphony #8 in D minor

- Nocturne (première recording) *

* Roderick Williams, baritone

London Symphony Orchestra/Richard Hickox

Chandos CHAN10103 72m DDD

Also released on Hybrid Multichannel SACD CHSA5016:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

Summary for the Busy Executive: Odd ducks, transformed into swans.

It becomes increasingly clear that the late Richard Hickox was probably the finest interpreter of British music in his generation. He risked much, and he won much. His early death came as a surprise to his admirers and cut off his Vaughan Williams symphonic cycle (he missed numbers 7 and 9), one of the landmarks in that composer's discography. Hickox had deeply rethought every score and even offered "new" versions, like the original "London" Symphony, rather than the composer's last revision. I would have loved for him to have plugged in the missing gaps. I've always thought the Seventh the weakest of the symphonies and the Ninth the most enigmatic. What would Hickox have made of them?

Gustav Holst, VW's great friend, died in the Thirties. Both composers regularly submitted their manuscripts to one another for criticism. VW felt the loss of Holst his whole life and absorbed Holst's influence even after the latter's death. He absorbed without imitation, however, and gave back almost as good as he got. I find Holst's influence especially strong in the Sixth Symphony. Some commentators have seen the score as hearkening back to the Fourth, but I think they inhabit two different worlds. The Fourth storms and rages and mourns. The Sixth – while not short on passion – is mainly very, very strange, far more nightmarish than its predecessor. I hear bits of Holst's Hammersmith, Egdon Heath, and even "Mars" in it. This doesn't include the oddities that Vaughan Williams has thought up all by himself.

The work, in four substantial movements, plays without a break, I'm sure challenging the players' stamina. The first movement begins with a tumble into controlled chaos. Its music is in both e minor and f minor, a harmonic analogy to the melodic opening D-flat/C dissonance of the Fourth symphony. Although nobody could reasonably call the work atonal, the sense of key stays extremely fluid throughout the movement. The opening tosses out a slew of ideas, one after the other, obsessing on a minor third, before it settles into a "galumphing" scherzo, a theme that splits into related grotesque and lyric parts. Thematic shapes, though dramatic and memorable, are hardly singable (or so you'd think). Even more disquieting is a rhythm that lurches and staggers about, with frequent difficult syncopations and scrappy phrasing. Vaughan Williams rarely gets credit for his considerable invention in rhythm. It may approach chaos, but it remains under firm control. It thrashes about until, just a bit short of the end, it takes the lyrical part of the "scherzo" and harmonizes it in pure, radiant E major, temporarily lifting the music out of its funk. The opening blares for the last time, and the lower instruments of the orchestra settle on a low E.

Out of that low E comes the second movement in B Flat minor, a tritone away and, like Holst's "Mars," a study in obsession. It insists on a "rat-a-tat" rhythm. Eventually, that idea fades out for a while. The lengthy interlude treats some of the shapes (which will reappear as the main matter of the finale) in a melancholy way. The "rat-a-tat" sneaks back in, signaling something ominous. It finally bursts out in a hammering climax, the most brutal part of the symphony. It loses strength, and an English horn solo takes over, ending alone over the timpani tapping out the "rat-a-tat."

This leads immediately to the scherzo (really more of a quick march), which to me revisits Satan's music in the composer's ballet Job. The tritone (also known as "the devil in music") figures prominently in the themes. The tenor sax has the same kind of sardonic commentary as the ballet. The symphony premièred with an earlier version of this movement, and it actually received a recording led by Boult in 1949, which might still be available somewhere on EMI. The composer revised his scherzo in 1950, and it's a real lesson in incisive revision. Things that seemed a bit fuzzy tighten into sharp focus. Again, after the big climax, the energy drains out of the movement, and we arrive at the finale via a held note on the bass clarinet.

The finale is one of the strangest in the symphonic literature. Fugal, marked pianissimo, without crescendo and without expression, it gave rise to commentary about the symphony as Vaughan Williams's vision of a world devastated by nuclear war. It's like watching smoke rising from a waste land. The composer, who usually never said anything one way or the other on extra-musical meanings discovered by others, was stung to reply that "It never seems to occur to people that a man might just want to write a piece of music." However, he did admit in a letter that he had in mind Prospero's lines "We are such things as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep." His widow quoted him characterizing the movement as "an agnostic Nunc dimittis." Vaughan Williams was in his 70s when he completed the score. It's reasonable to assume that death might have been on his mind, although he seemed to believe that death happened to other people and since he had lost loved ones since childhood, he had become accustomed to it. Even so, his beloved first wife, Adeline, had for years suffered from crippling arthritis. Mostly bedridden, she hadn't many years longer to live.

The Symphony #8 (1953) comes from the composer's last period and reflects an expanded interest in sonority. Again, one notices an oddness in each movement's conception. The first the composer himself described as "seven variations in search of a theme." The second is for winds only, the third for strings only. The fourth features the percussion. Because of this – and probably because of the composer's rather jokey program notes – critics and conductors have underestimated this symphony as "light," a composer's holiday. It certainly doesn't rail like the Sixth or console like the Fifth, but "light" is really a relative term. Bernard Haitink (EMI 57086), likely because uninfluenced by the British critical climate and performing tradition, presented the symphony in a brand-new light. He seemed to ask what it actually means to write variations without a theme. He emphasized Vaughan Williams as a symphonic thinker. I suspect Hickox learned something from this. This isn't a variation set as much as it is a symphonic movement varying two ideas: the opening little fanfare (two leaps of perfect fourths, a second apart) rising out of nowhere and its continuation in a swaying figure. Before this performance, I had paid so much attention to the "variations," I neglected the overall structure. In other words, Vaughan Williams arranges his "variations" to come up with something very similar to sonata: exposition, development, and brief recap and coda.

The scherzo, another quick march and scherzo, follows. It has some of the pertness of Prokofiev, but it also revisits and streamlines some of Vaughan Williams's music of the Twenties, like the Toccata Marziale and, in the trio, the Pastoral Symphony. It disappears in a poof!

Michael Kennedy in his still-standard study of the composer's music noted Vaughan Williams's penchant for burying his most personal statements in so-called "minor" work and specifically cites the "Cavatina" slow movement for strings in this score. Vaughan Williams thought of Bach as the greatest composer of all and, as works like the "Rhosymedre" prelude for organ and the Concerto accademico demonstrate, actually learned something from him. Vaughan Williams came up with an original theme and noticed a resemblance to the chorale "O sacred head now wounded" from Bach's St. Matthew Passion. The two tunes to some extent fused in his mind. This results in a pure Vaughan Williams pastoral meditation, in which bits and pieces of the chorale occasionally flash and merge with the rest of the music. How people could have considered this music lightweight amazes me.

A rondo, the "Toccata" finale features "all the 'spiels and 'phones known to the composer." After attending a performance of Turandot, he added a couple of tuned gongs. In short, the work bristles with most, if not all, of the standard percussion instruments capable of producing a definite pitch. The result, however, is bright not brutal, airy not aggressive. The music for me breathes the same emotional air as the finale from Isaiah of Dona nobis pacem and the passacaglia of the Fifth Symphony.

As in other releases, Hickox includes a piece by the composer you probably haven't heard before or even knew existed, other than in books. In 1908, roughly the time of his study with Ravel, VW projected a series of three "nocturnes," based on poetry by Walt Whitman. He completed one and sent it off to a singer in hopes of a performance. He heard nothing back and basically went off the boil for the project. One can see why. He tries for something like Ravel's Shéhérazade and comes up with a hot mess of moaning around with little direction. Ravel said of VW that the Englishman was the only one of this his students "who doesn't write my music." He probably never saw this piece. At any rate, the thoroughly characteristic Sea Symphony and the incidental music to The Wasps are about a year away. The difference between those and this is such that you can't believe it's the same composer. Still, the work interests a VW fan like me who, with the intensity of a stalker, wants to know everything. It gets heavier with counterpoint as it proceeds and ends in a blaze of brass and bells.

Hickox gives my favorite readings of the two symphonies. He's clear, elegant, even athletic and unties the knots in these oddly-shaped works. The playing of the London Symphony Orchestra is ravishingly good, gorgeous in tone, attentive to detail, alive to ensemble. Roderick Williams continues to demonstrate he's one of the finest singers around, but not even he and Hickox can save the Nocturne. Chandos's recorded sound adds to the beauty of these performances.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz