The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Finzi Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

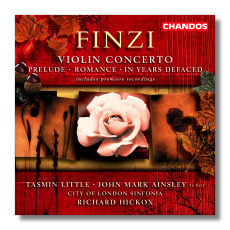

Gerald Finzi

Vocal and Instrumental Works

- In Years Defaced

- Prelude for String Orchestra

- Romance for String Orchestra

- Concerto for Small Orchestra and Solo Violin

John Mark Ainsley, tenor

Tasmin Little, violin

City of London Sinfonia/Richard Hickox

Chandos CHAN9888 54:34

Summary for the Busy Executive: Proud songsters.

I always think of Gerald Finzi as the English Fauré, mainly because of his songs. Both composers have the gift of following the twists and turns of often complex poetry without resorting to faux -recitative or to dropping a melodic thread. Finzi's songs sound right, rather than labored, although he often spent many years getting them into that state. His concern was always that his music sound "natural," and this and his self-criticism both lengthened times to completion and also reduced his output. He preferred to keep things in his desk drawer rather than to force them. Of course, financial independence (his father made money in shipping) allowed him this option.

Very widely read, Finzi had a special affinity for the poetry of Hardy and produced at least three major song cycles to Hardy's words. The song group In Years Defaced culls stuff from various sources. In many ways, it's a tour-de-force. Like Fauré, Finzi preferred the baritone voice and wrote most of his songs for piano accompaniment. He orchestrated "When I set out for Lyonnesse" (from the Hardy baritone cycle Earth and Air and Rain) in the Thirties for tenor Steuart Wilson as kind of an encore to a concert featuring the premières of 2 Milton Sonnets and A Farewell to Arms. Recently, someone had the bright idea of orchestrating more and commissioned the composers Judith Weir, Anthony Payne, Colin Matthews, Christian Alexander, and Jeremy Dale Roberts to choose and orchestrate other Finzi songs: "To a Poet a Thousand Years Hence," "In Years Defaced," "Tall Nettles," "At a Lunar Eclipse," "and Proud Songsters." The results are all at least very good, and in the cases of the first three orchestrators, at any rate, very Finzian. That is, they sound like other orchestrations by the composer. Furthermore, considering the wide perimeter of choice and the independence of each composer, I'm surprised that the songs all seem to go together. Perhaps Finzi was drawn to a certain outlook or mood from work to work. Finzi's music has often been lumped into English Pastoralism, and with good reason. But there's also an intellectual distance - as there is in Hardy and Housman - between the perceiving sensibility and the pastoral scene, a duality also reflected in Finzi's Jewish background and his identification with "Englishness."

Finzi had more trouble with instrumental music than with vocal. There aren't that many instrumental works to begin with. He suppressed or ruthlessly excised many early efforts, including a piano concerto. The Prelude of 1928 he intended as part of a chamber symphony. He completed only one more movement - The Fall of the Leaf. The Romance, from 1929, was originally going to be part of a string serenade. Again, Finzi never completed the larger work. The Prelude has a bit of the sound of Elizabethan virginal music. The Romance, on the other hand, sings in a characteristically warm way, familiar to those who know his late clarinet concerto.

The violin concerto undergoes the same sort of history. It begins in 1925, so it's fairly early. Finzi disliked the first movement and threw it away. However, spurred by Vaughan Williams, he wrote another. Vaughan Williams conducted the once-again complete (though different) violin concerto in 1928. Again, the first movement failed to please the composer, and he consigned it to oblivion by listing only the slow movement as an "official" work. This became the Introit for solo violin and chamber orchestra. Composers are generally no more perceptive about the quality of their own work (either way) than anyone else. You listen to the first movement and wonder what the hell Finzi was thinking of. It's a wonderful, lively movement, similar in spirit to the neoclassical works of Vaughan Williams and Holst - the Concerto accademico, the Fugal Concerto, and so on - but speaking in Finzi's own accent. The gorgeous slow movement will break your heart, it's that beautiful, full of both regret and acceptance. I find the finale the weakest movement of the three, but there's nothing seriously wrong, except that you wish there were more of it. While not at the level of the concerti for clarinet and for cello, this work should strengthen the hearts of old fans and win those of new ones.

Hickox plays this music from the inside - basically, the only way to play it. I think he's inherited Boult's mantle as an advocate for a certain type of British music - the Vaughan Williams wing - although he also does well with Britten, Walton, and Tippett. At his best, he sings. John Mark Ainsley is a Gerald English tenor, rather than a Richard Lewis or Peter Pears one. It's light, but it's clear and flexible. Occasionally, he forgets himself and swoops and scoops at moments of Great Emotion. At this point, however, it amounts to little more than an imported affectation from Italian opera - something Finzi really doesn't need - and Ainsley can do something about it, before it becomes an ingrained habit. Perhaps he can think more of the beauty of a note hit straight on. Tasmin Little does well, but the Finzi concerto doesn't let the spotlight shine on a soloist. The music's mainly the thing. However, she does wonderfully well in the concerto's slow movement. She "gets" it.

Copyright © 2004, Steve Schwartz