The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Vaughan Williams Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

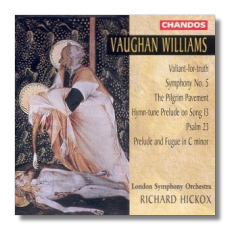

Ralph Vaughan Williams

- Valiant-for-truth *

- Symphony #5 in D Major

- The Pilgrim Pavement *

- Hymn-tune Prélude on Song 13 by Orlando Gibbons (arr. Glatz)

- The Twenty-third Psalm * (arr. Churchill)

- Prélude and Fugue in C minor

* Richard Hickox Singers

London Symphony Orchestra/Richard Hickox

Chandos CHAN9666 70:48

Also released on Hybrid Multichannel SACD CHSA5004:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

Summary for the Busy Executive: Redefining beauty.

Vaughan Williams rarities nestle against a recording of perhaps his most popular symphony. Most of the items on the program link one way or another to Vaughan Williams' nearly life-long fascination with Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. The work appealed to the composer not solely because of its magnificent prose, but also because of its close ties to the intellectual background of the Fabian Socialist movement during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The Pilgrim Pavement and the Hymn-tune Prélude on Gibbons are absolutely new to me, and I've made Vaughan Williams an active part of over forty years of collecting recordings. I can find no mention of them in standard reference of Kennedy's Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams, although they get brief mention in R.V.W., Ursula Vaughan Williams' biography of her husband. The composer wrote The Pilgrim Pavement on commission from the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan. As the liner notes point out, unusually for him, he set words that he didn't choose. He thought he needed the occasional discipline. The words are one small step above bloody awful, and any power the piece has derives solely from the composer. Apparently, he struggled with the text and later tried to have his anthem withdrawn. Other signs of Vaughan Williams' sense of discipline come to the fore in the suitability of the work for good amateurs, choristers and organist. Although professionals most likely would do better, it's something that still comes off for a decent church choir, and it has musical interest besides. It may not rise to the level of Vaughan Williams' best, but it fascinates me anyway for the way it sets the poetry. Vaughan Williams uses it as an occasion for an extreme approach to reconciling speech rhythms and musical meters. The poet uses hymn metrical patterns for the text, which suit a regular musical phrasing. Vaughan Williams, however, comes up with one irregular phrase after another, at one extended point, moving along in either seven or five large beats in a poetic meter of four. The speech rhythm wins out over the meter. This tendency became more pronounced as Vaughan Williams got older, culminating in his Pilgrim's Progress "morality" (as he designated his opera) and in the Ten Blake Songs.

Vaughan Williams wrote the Gibbons Hymn-tune Prélude for Harriet Cohen, the same musician for whom he composed his piano concerto. Obviously, he admired her playing. Here we have the piano miniature in a composer-approved arrangement for strings by one Helen Glatz. It's three minutes of pure lovely, a typical Vaughan Williams elaboration of a simple figure against a tune in long notes, like the better-known Prélude on "Rhosymedre." Listening to the work and especially to the flowingly changing background-foreground relationship of accompaniment and tune puts me strongly in mind of the Bach chorale Préludes.

John Churchill has arranged part of Act IV of The Pilgrim's Progress ("The Shepherds of the Delectable Mountains") as a setting of Psalm 23 for mixed chorus and soprano solo. It's a lovely job, too. The opera is unlikely to receive a staging at a theater near you any time soon, and this kind of tinkering strikes me as as good a way as any to disseminate the music to audiences. I should say, however, that Churchill necessarily has simplified the original considerably. The opera scene is a contrapuntal glory with the psalm ("The Voice of a Bird") providing background commentary (like Bunyan's own marginalia of Biblical quotation) to Pilgrim's wonder at the Delectable Mountains and with a solo string group singing like birds over the orchestra – a Vaughan Williams take on Wagner's "Waldrauschen." Churchill works with great acuity. I complain only that it sounds like Vaughan Williams' music, but not particularly like Vaughan Williams' choral music. I find an over-reliance on standard choral strategies of tune accompaniment, which, after a certain early point, Vaughan Williams abandoned. In the late a cappella choral music especially, each part is equally important. Nothing stays completely in the background.

The Prélude and Fugue in c has been recorded in its full orchestral dress at least once before, conducted by Vernon Handley. Vaughan Williams originally wrote them as organ pieces as early as 1921 and orchestrated them in 1930. Michael Kennedy once pointed out that Vaughan Williams tended to innovate and change in relatively small pieces. Here, we can discover signposts in the Prélude to such works as the Fourth Symphony (1934) and in the fugue to Flos campi (1925) and to the passacaglia that closes the Fifth Symphony (1942). Indeed, the fugue's subject is almost a twin to the opening theme of Flos campi. The treatments, however, differ startlingly, Flos campi (with its bitonal opening) owing less to traditional counterpoint and more to a vision of simultaneous planes of sound. Historically, the Prélude and Fugue shows that Vaughan Williams' development didn't really progress linearly. The rough view of his music of the Twenties – "pastoral" and "contemplative" – fails to take in the many works that fall outside: the violin concerto, Sancta Civitas, Old King Cole, and this one. Because of the Fourth Symphony, writers tend to view the Prélude and Fugue as an adumbration, rather than as something aesthetically complete in its own right. It certainly doesn't have the finish of the symphony. In other words, Vaughan Williams mined the musical vein deeper later on. However, it's still a crackling good piece.

Vaughan Williams wrote Valiant-for-truth on the death of a close friend, Dorothy Longman. This is the first fully satisfactory commercial recording I know of – amazing evidence of ignorance and neglect. The motet ranks with such acknowledged masterpieces as the Mass in g and A Vision of Aeroplanes – in other words, as great a choral work as Vaughan Williams ever achieved. It's difficult as sin to perform – mostly quiet, practically at the edge of hearing, and slow, with long stretches of unison singing, and then blazing counterpoint at the end as "all the trumpets sounded for him, on the other side." Intonation, a command of decrescendo and true unison, and just plain running out of breath become the technical challenges singers must meet. My favorite recording was made by amateurs, and since you'll never hear it, there's no point in my going on about it. The Hickox, however, is probably as good as we are going to get, and it's by no means terrible. It's just that the amateurs had months' more rehearsal time in which to master interpretation than most professionals get. They sang as if the music had bonded to their insides – more than a fine performance. The Hickox Singers do well enough, conveying the stature of the piece, but their dynamic range is way too constricted. They never really get soft enough, and their intonation, although solid, never contributes to the ecstasy of the positively magical chord progressions the composer discovered. I hope, however, that the Hickox recording makes this work better known and encourages many more performances.

If you already own Barbirolli, Boult, or Previn, do you really need this recording of Vaughan Williams' Fifth? I would say so, emphatically. This performance goes to the front of the line, even ahead of those earlier classic accounts. It's warmer than Boult, not as passionate as Barbirolli, and far more assured in its textural balance than Previn. Frankly, I was surprised. While I've admired Hickox in Vaughan Williams repertoire, many times something seemed to go wrong with his recordings. The recent "London" Symphony suffered I think because of the use of the composer's original score, rather than the revision. While Hickox performed a valuable service in making the score known, the diffuseness at times of the composer's first thoughts played havoc with the narrative flow. Hickox's accounts of Dona nobis pacem and Sancta Civitas were marred by the self-indulgence of Bryn Terfel, who seemed incapable of putting out a line free of scoops and swoops.

Hickox offers something I really didn't believe possible: a new view of this symphony and perhaps of the composer himself. We seem to have gotten more such recordings recently, with Haitink penetrating the scores of the Eighth and Ninth Symphonies and finding new valid interpretive threads. Vaughan Williams began the Fifth in his late sixties. He had been working for several decades on his theater version of The Pilgrim's Progress but found himself a long way from the finish line. He had no way to know whether he would ever finish and so decided to adapt some of the ideas to an orchestral work (in the Forties, he also composed a radio version that used some of the opera's material). Hickox's account gains immeasurably from the fact that he obviously knows the opera very well (he has recorded a version for Chandos – CHAN9625(2) – which I haven't heard).

Most conductors tend to sentimentalize, viewing the symphony as one long benediction. Light in Vaughan Williams' music seldom comes without dark, however, and the symphony, like the opera, has its demonic moments. In the opening movement, for example, toward the end of the second subject group (for those of you keeping your sonata score card), there sounds a descending "Phrygian" third (Eb – Db – C), associated in the opera with the forces of Hell, especially Beelzebub. It turns out that Vaughan Williams relates this idea to the serene horn call which begins the work. Hickox nails these things, to the extent of bringing out the demonic motive in the first pages of the score – something I've never heard before. Hickox also emphasizes that this is a contrapuntal symphony. Many critics seem to regard the composer as a mere rhapsodist. While he has his ecstatic moments, Vaughan Williams is really one of the most solid builders around. He has so completely mastered counterpoint, that not only do many people miss it, so completely does it serve expression, but he actually has the reputation as a weak contrapuntalist. The exposition of this symphony, for example, is usually taken as singing pure and simple. Actually, the composer has conceived it as the sounding of similar musical lines at slightly different times. The techniques of canon and stretto he applies in unconventional ways. This is not pseudo-Baroque pastiche. Instead, one thinks of several singers starting with a similar idea and individually "winging it." Again, Vaughan Williams isn't usually interested in contrapuntal display for its own sake. He has thought of music first. His finely-honed contrapuntal skills allow him to think of more possibilities and to intensify an essentially melodic form of expression. In this, he reminds me of Brahms, Mahler, Nielsen, and, his favorite, Bach. Hickox captures the emotional tone perfectly from the opening horn call: he always holds something back, and the reserve paradoxically implies greater depth. It's a reading of impressively mature balance.

The second movement, a scherzo, riddled with allusions to the opera's "Vanity Fair" sequence, requires great delicacy from the players, which Hickox gets. Yet no one walks on eggshells. It's a positive control that comes from, again, great power held in reserve, so that the broader moments rise naturally from the more rhythmic passages. I've heard performances in which the conductor gooses the emotional level, and it almost never convinces me. The movement becomes too disjointed. Hickox's reading is of a piece.

In the slow third movement, Hickox triumphs. I prefer him even to Barbirolli here. The composer uses ideas from the "House Beautiful" sequence in the opera and also from Pilgrim's cry of "Save me, Lord! My burden is greater than I can bear." The opening is probably note-for-note from the introduction to the "House Beautiful." One of the glories of the movement is a remarkable "free-for-all" conversation among the winds, which the players deliver with great beauty and grave reserve. There's nothing over-the-top here or calling attention to itself. Everyone seems to be "just singing." The movement expresses mainly serenity touched by sadness, with the typical Vaughan Williams contrast of spiritual agitation. The climax of the movement (related to the alleluias of Vaughan Williams' early hymn "Sine Nomine") not only rocks, but Hickox and the orchestra's subsequent decrescendo is glorious. Hickox also has mastered the end, with an incredibly slow tempo that never, ever bogs down. The orchestra maintains intensity and the sense of forward movement to the final note.

The "Passacaglia" finale reworks ideas not only from the opera ("The Arming of the Pilgrim"), but from Vaughan Williams' oratorio Dona nobis pacem ("Nation shall not lift up sword against nation" and "Open to me the gates of righteousness") and from his hymn setting of Bunyan's "He who would valiant be." The movement poses mainly two challenges: clarity of the counterpoint and the return of the first movement's material. Hickox meets the first, but not entirely the second. However, nobody else quite gets it either. I've studied the score for years, but I still have little idea why the return of the opening horn call causes conductors to stumble. On paper, it grows necessarily from the passacaglia variations. Although structurally an important point, it is fortunately short, and, once it ends, conductors find their feet again. However, Hickox does make clear the relationship between the main theme of the passacaglia and the first-movement material. The symphony ends with an extended fantasia on the passacaglia's ideas, and once Hickox reaches this point, equilibrium is restored. We end beautifully.

I can't recommend this CD highly enough. Valiant-for-truth alone would make it worth your while, but Hickox's account of the symphony ranks as a milestone in the recording of Vaughan Williams' music. The sound is wonderful.

Copyright © 2001, Steve Schwartz