The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Grainger Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

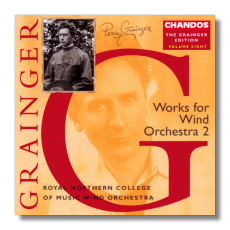

Percy Grainger

Grainger Edition, Volume 8

Works for Wind Orchestra 2

- The Power of Rome and the Christian Heart *

- Children's March *

- Bell Piece *^

- Blithe Bells

- The Immovable Do

- Hill Song I

- Hill Song II

- Irish Tune from County Derry *

- Marching Song of Democracy

^ James Gilchrist, tenor

Royal Northern College of Music Wind Orchestra/Clark Rundell

* Royal Northern College of Music Wind Orchestra/Timothy Reynish

Chandos CHAN9630 65:04

Summary for the Busy Executive: Re-thinking.

This CD boasts several recorded premières, but of different versions of well-known pieces. Grainger tinkered with his music to an unusual extent, sometimes to re-interest performers in his music (Stokowski, for example, in classic accounts), sometimes to find the best, or even another, expression of the basic ideas. I'm a Grainger nut, but, even so, several of the pieces are new to me: The Power of Rome and the Christian Heart, Bell Piece, the Hill Song I, and the Marching Song of Democracy. Some of the titles here are also on volume 4, also devoted to Grainger's wind ensemble music, but in première recordings of new versions startlingly different from their more familiar siblings. Chandos seems determined to record everything, thank goodness. Perhaps Grainger will finally get his due as an extraordinarily interesting musical mind (he pioneered, among other things, graphic music and synthesized music), rather than as a bizarrely twee miniaturist, with all the condescension that implies.

While volume 4 concentrated on Grainger's genius as a setter of folk tunes, this one covers mainly original work, including some of Grainger's longest pieces. At about twelve minutes, The Power of Rome and the Christian Heart certainly qualifies. The piece comes from Grainger's experience in the American army during World War I. He worked as a bandsman and, indeed, caught his enthusiasm for large wind ensemble here. Grainger intended it to portray, oddly enough, his pacifism and the individual conscience acquiescing to or defying the power of the State. The music doesn't overtly describe any of this but springs from those thoughts. Grainger remained proud of it, although its highly chromatic harmonies began to pall on him as "conventional." I have no idea what he means. From its opening measures, the progressions – and the piece's ideas are (unusually for Grainger) mainly harmonic – come from so far off the beaten track, you may find yourself well wondering how on earth he came up with them. Grainger writes chromatically almost as if Liszt and Wagner had never lived. These harmonies, like Prokofieff's, come from the twentieth, rather than the nineteenth century. The progressions have almost a somatic result, as the muscles in your head try to get them around your mind. One also notes the unusual, beautiful orchestration, from the opening solo for the harmonium to the inclusion of harp to the fondness for the acidic sound of double-reed winds.

Grainger loved introducing new sonorities into his wind and orchestral works. The Children's March ("Over the hills and far away") is a case in point. At any rate, the version here bears little resemblance to the one usually heard. Grainger wrote it for the Goldman Band (Goldman's account, with Grainger at the piano, used to be available, but I can't find it currently in the U.S. or the U.K. ; I have it on an old Decca LP), but Richard Franko Goldman, the director, apparently left out certain features of the scoring, although what remained was certainly unusual enough. Not only does Grainger call for piano, harp, and some "tuneful percussion" (by which Grainger usually meant bells, glockenspiels, celestas, xylophones, marimbas, vibraphones, and chimes), but he also asks that players not tootling at the moment sing on "oh" during the trio. That moment will open you up like a can of tuna. The themes in themselves throughout are joyous and give off the excess physical energy so much a part of the composer almost to his death.

Grainger takes Bell Piece from Dowland's lute ayre "Now, oh, now I needs must part," a great Grainger favorite. He used to sing it before going to bed. The piece opens with a solo tenor singing to a relatively straightforward piano accompaniment. As the tenor finishes, the clarinet steals in and we get a more and more Grainger-like fantasy (or, in his words, "free ramble") on the tune. The ramble strays very far indeed. Why the title? In this version, Grainger added a part for (I think) glockenspiel so that his wife Ella could play during performances.

The better-known Blithe Bells gives Bach's "Sheep may safely graze" approximately the same treatment, this time with a whole mess of "tuneful percussion." He originally wrote it for "elastic scoring" (yet another Grainger innovation) – that is, any instruments in the right range for the parts and, in certain cases, certain parts could be omitted. The band version comes from 1931.

Grainger, a piano virtuoso (Grieg preferred him to all other soloists in his concerto), hated the piano and arranged several of his works for it almost always at the insistence of his publisher. However, he had no such animus toward the harmonium or, later, the early electronic instrument, the Solovox. They produced the sounds similar to the ones he pursued in his quest for electronic music. He owned several harmoniums. While practicing on one of them, he noticed that mechanics of one of the keys, a high C, had gotten stuck, emitting a fixed drone. Rather than immediately repair it, he composed music that took an ever-present high C into account and called the resulting work The Immovable Do. That drone seems tailor-made for Grainger's side-slipping harmonies. It only gradually dawns on you that the C constantly, or nearly, whistles, throughout the main musical business. The band version here comes from 1939.

A lot of wind players know the Hill Song II, originally written in the 1900s. Whatever happened to Hill Song I? It finally shows up here, over twice as long as its successor. Some of the material is the same. In the liner notes, Grainger maven Barry Peter Ould contends that the later piece presents all the faster material, omitting the slower, "dreamier" contrasts. To me, the songs radically differ, although they share several themes. Hill Song I experiments with scoring by omitting every single reed from the ensemble. Grainger liked this version and considered it one of his "most perfect" pieces. I think it ultimately lacks enough contrast of timbre so that all that sharp sonority begins to sound oppressive and thick. This no longer remains an issue in the second Hill Song, which also benefits from rather energetic concision. It has less than half its prototype's length.

Grainger loved a great melody, probably reasons behind his admiration for Bach, Grieg, Ellington, and Gershwin, as well as for folk music. He apparently went gaga over the "Londonderry Air" (a.k.a. "Danny Boy"). He arranged it every which way, including for voices, in which every part can be sung on its own with perfect sense. This band setting comes from 1920. It is independent of all the others, including the better-known band version of 1918. Grainger scores for military band and, believe it or not, pipe organ. Makes marching a bit of trouble.

Rose Grainger, Percy's mother, exerted the greatest single influence on him. He got almost all of his attitudes from her. He was convinced of his genius because she was. The extraordinary relationship between mother and son (she procured his mistresses for him) was so strong, he didn't marry until she died. He inherited his mother's anti-Semitism, although he championed Jewish musicians. However, he also inherited her love of democracy. Percy could have easily turned out a proto-Nazi, had it not been for Rose. At any rate, he wrote the work in the early 1900s originally for chorus and orchestra, a practical accommodation to his rather nutty original conception – men, women, and children singing and whistling outdoors to the rhythm of their marching feet. Grainger's strong distaste for the normal techniques of development results in a work with enough ideas for at least three more. Fortunately, Grainger could write wonderful, idiosyncratic melodies himself. He didn't merely collect. In 1948, he made the current version for wind ensemble and dedicated it, appropriately enough, to his long-dead "darling mother, united with her in loving adoration of Walt Whitman." Even without the marching feet, this is in spirit open-air music. It takes big breaths and swings its arms in step. It just catches the listener up and sweeps him along – an "unstoppable tide," Ould calls it and hits the nail on the head.

Before the Grainger series, I'd not heard of the wind orchestra of the Royal Northern College of Music, nor of Reynish and Rundell. They play at least as well as any other wind ensemble I've heard, including Fennell's Eastman-Rochester. The two directors have the measure of Grainger's musical quirks and manage to turn somewhat loose rambles into purposeful journeys.

Chandos' entire series has been so far first-rate and has even raised the bar on what I thought first-rate to be.

Copyright © 2003, Steve Schwartz