The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

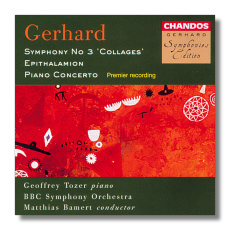

Roberto Gerhard

Orchestral Works

- Symphony #3 "Collages"

- Concerto for Piano and Strings *

- Epithalamion

* Geoffrey Tozer, piano

BBC Symphony Orchestra/Matthias Bamert

Chandos CHAN9556

Executive Summary: Music of great integrity, power and drama, composed within a context of a highly personalized application of serial techniques. The Third Symphony is one of the most convincing works to combine acoustic instruments with electronically generated sound. If you have much interest in exploring music since 1900, and are looking for a potentially rewarding challenge, this disc could be for you.

Roberto Gerhard was born in Catalonia in 1896 and died in Cambridge in 1970. The range in his musical expression was as wide as the difference in the harmonic vocabularies of his teachers, from Granados and Pedrell to Schoenberg. Gerhard's early works like the ballets Don Quixote and Soirees de Barcelone display his interest in the nationalistic music of Catalonia, while the works after his opera The Duenna such references take a back seat to the application of serial techniques to his expression. Susan Bradshaw, writing in the New Groves, brilliantly summed up Gerhard's music when she wrote, "The one vital characteristic of Gerhard's work which was fundamental to every piece of music he wrote was the basic fact of rhythmic pulsation. It was this apparently alien force which, once harnessed to the cause of his serial ideas, enabled him to give such rare and powerfexpression to his vision of music as a buoyant art: as the technique of setting sounds in motion and of propelling them through the space of their collective time span."

Those notions are clearly found in Gerhard's Third Symphony "Collages." The drama in this work is so clear that it makes it an excellent introduction to his late style. Gerhard pointed to his experience of an airplane flight from America and seeing the sun rise at 30,000 feet as the initiation of his inspiration for the piece. The opening is filled with all sense of drama and wonder one would expect from a work which derived it compositional motivation from such an experience. This work combines electronically prepared, prerecorded sound with the orchestra. This is not electronic music which tries to imitate the sounds of the orchestra, but rather it is music which explores a more idiomatic notion of the potentials of the medium within the context of the limitations of the technology of the late 1950s. The two forces are combined with such sensitivity and craft that this work remains for me one of two or three such compositions that makes a convincing argument for the combination of what might be seen as two distinct idioms. While you are almost always aware of the electronic sounds when they are present, their presence seems totally logical to the compositional discourse. This is brilliant music. Since I first heard this work some 30 years ago, the closing measures are one of those profoundly moving moments in music that has remained etched in my mind.

The Concerto for Piano and Strings is amongst Gerhard's transitional works. Serialization of pitch is often used to prevent anyone pitch from having dominance over another. Continuing that notion one would need to avoid rhythmic patterns which would place repeating emphasis on one pitch, leading a composer like Boulez, in his work Structures to serialize many parameters including rhythm, tessitura and dynamics to follow that notion to its logical conclusion. Rhythmically Gerhard's Concerto relies clearly on his Catalonian heritage which would place that repeating emphasis from time to time on a singe pitch, yet the pitch organization has its origins in serial technique, which clearly illustrates that "alien force" Bradshaw points out in her writing about his music. The second movement "Diferencias" or fantasy variations, is one of the most attractive, almost seductive moments that I have ever encountered in his music. His quote of the "Dies Irae" from the Mass of the Dead brings an odd notion to music of the opening of the movement which is so seductive in character. The brisk final movement is filled with some perhaps contradictory notions; a reference to his expatriation? He combines the folk music of Catalonia and the opening three pitches of "God Save the King," all within the context of the application of serial techniques.

Epithalamion is a late work dating from 1966. The manuscript quotes Psalm 18 "In them hath he set a tabernacle for the sun, which is as a bridegroom coming out of his chamber (and rejoiceth as a strong man to run a race)." However, I find it difficult to find any programmatic references in the work. In his program note Bernard Benoliel points towards Arcana by Varèse as a stylistic antecedent to Epithalamion. The illusion does not seem all that inappropriate and in a sense provides a very different perspective to Gerhard's music, one that I had never considered. Once again, quoting Bradshaw on the subject of the music of Gerhard, "his music evolved a new means of propulsion, marking the tension or relaxation of its progress by the density or clarity of its textures; by passages of crowded eventfulness set against those whose events are so distanced that time seems to stand still; by moments of insistent rhythmic activity that dissolve into overlapping layers of unarticulated vibrations." All the while this remains music that is filled with both great violence and great poetry.

The recorded sound and playing of the BBC Symphony are excellent. To my ears Bamert has a firm sense of the poetry of the music, especially in the second movement of the Concerto, yet he fails to capture the power and violence in the music. I found the choice of tempo in the last movement of the Concerto to be too slow. As far as I know this is the third recording of Collages. The first, also with the BBC Symphony, conducted by Prausnitz has my vote for the best interpretively, yet the precision in the playing is better in the Bamert recording. Both BBC Symphony recordings benefit from a more expansive acoustic than can be found in the recording on Auvidis conducted by Victor Pablo Perez. His interpretation seems to an attempt to explore the structure, with Prausnitz finding the fullest range of expression, perhaps at the expense of precision in the execution, while Bamert seeks out a more traditional notion of line. Obviously there is more that can be said interpretively with this work. Even with my concerns over Bamert's realizations of these scores, this disc is a wonderfintroduction to the late works of Gerhard.

Copyright © 1998, Karl Miller