The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Suk Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

SACD Review

SACD Review

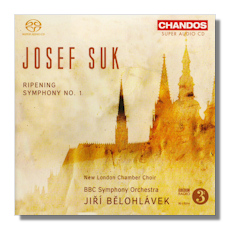

Josef Suk

- Ripening, Op. 34 (JSkat 70) *

- Symphony #1, Op. 14 (JSkat 40)

* New London Chamber Choir/James Weeks

BBC Symphony Orchestra/Jiří Bĕlohlávek

Chandos CHSA5081 Hybrid Multichannel SACD

There's already a good chance that this CD will go some way towards destroying Suk's reputation. He's usually thought of as one of those composers, more than merely proficient, with whose work you ought to be more familiar; a composer best known for his violin (and piano) playing; Dvořák's son in law; and as Josef Suk, the violinist's, grandfather. He was born in Bohemia in 1874, began serious composition in his teens studying with Dvořák while at the Prague Conservatory, at which institution he eventually taught… Bohuslav Martinů was one of his pupils. Orchestral and instrumental works occupied Suk the most during a long career that lasted until he died in 1935. His music is romantic and shows folk and nationalist influences, though it's also impressionist in flavor. But how good is Suk's music itself?

Here's a CD with expert accounts of two of the composer's most inspired and impressive symphonic compositions. Suk worked on Ripening (Zrání) for five years, from 1912 to 1917. It was one of four tone poems written while he was at the height of his powers but also during years when he suffered greatly at the loss of both his wife, Otilka, and her father. It's a passionate attempt to express what the soul needs to find and draw on in order to overcome loss.

Though the BBC Symphony Orchestra under its conductor, Jiří Bĕlohlávek, with the New London Chamber Choir don't linger, there is plenty of emotion in their approach. Although their account respects the emotion, the wax and wane of hope, they never indulge melancholy, since Suk didn't. Thereby they reflect exactly what Suk intended – a ripening, or re-elevation of hope in the face of tragedy. After all, the poem whose words inspired Ripening (and which are reproduced in the liner notes) are from a cycle by Antonín Sova called Žnĕ (Harvests), which imply cycles, the results of events.

In their reading there really is as much hope as regret. But at the same time, their gently flowing sweeps of melody show awareness of what has made hope necessary. The tension is well achieved. Nor truly dissipated at the end. The participation of the choir is subtle. Nothing figurative or representational. Merely an atmosphere, a presence. A hint at the future. The recording balance supports this well.

The first symphony is a contrast. Much more positively tuneful; simpler, if anything; hints of Czech open strings and cadences. It was begun in 1897 and took two years to complete. It's not overly ambitious, at times shows the influence of both Brahms and Dvořák. Yet it has a substantial feel to it. There is variety, some sound instrumentation (the balance of strings, which are perhaps inevitably prominent, with woodwind in the first movement, and with brass in the second), melodies that are neither insistent nor too insipid.

The symphony is predominantly fast, three of the four movements being marked allegro. This seems to give the second, an adagio, all the more impact. Again, the BBC Symphony has the measure of the music at every turn. Their articulation is definite, uncompromising and sure. But the emotions and thoughts which they know the music aims to communicate are never forced onto us. Above all, the tempi and relative momentum that they give to movements and sections of movements indicate a sure appreciation of the symphony's overall architecture.

These are both works worthy of close and careful listening, eventually revealing more than might appear the case if they had been treated as second rate examples of late Romantic symphonic note-spinning. In their very reserve, determination and drive (qualities which Bĕlohlávek understands how to elicit so well) there's a purpose, a perhaps enigmatically-reserved purpose, which is pleasing to get to know.

There is only one other current recording of the first symphony – on Supraphon (3941) with Tomas Netopil conducting the Prague Symphony Orchestra. Of Ripening there is a clutch, but none so powerful as this one, nor any with this coupling. For those who still have a block where Suk is concerned, here's a good place to start. The acoustic is rich and full; the liner notes helpful with the text for Ripening. Well worth a close look.

Copyright © 2011, Mark Sealey.