The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Eccles Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

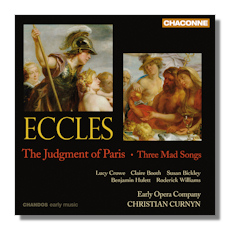

John Eccles

- The Judgment of Paris or the Prize Music, A masque:

- Symphony for Mercury

- From high Olympus, and the Realms above

- O Ravishing Delight!

- Fear not, Mortal: none shall harm thee

- Happy thou of Human Race

- Symphony for Juno/Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove, am I

- Symphony for Pallas/This way, Mortal, bend thy Eyes

- Symphony for Venus/Hither turn thee, gentle Swain

- Hither turn thee, gentle Swain

- Distracted I turn, but I cannot decide

- Symphony/Let Ambition fire thy Mind

- Awake, awake, thy Spirits raise

- Hark, hark! the glorious Voice of War…

- Oh what Joys does Conquest yield!

- O how glorious 'tis to see…

- Symphony

- Stay, lovely Youth, delay thy Choice

- Nature fram'd thee sure for Loving

- I yield, I yield, O take the Prize

- Hither all ye Graces, all ye Loves

- Three Mad Songs for voice & orchestra:

- Restless in Thought disturb'd in Mind 1

- Love's but the frailty of the Mind 2

- I Burn, I burn, my Brain consumes to Ashes 3

Claire Booth, soprano (Pallas and 2)

Lucy Crowe, soprano (Venus and 1)

Susan Bickley, mezzo-soprano (Juno and 3)

Benjamin Hulett, tenor (Paris)

Roderick Williams, baritone (Mercury)

Chorus of Early Opera Company

Early Opera Company/Christian Curnyn

Chandos Chaconne CHAN0759

In 1700, musical entrepreneurs in London announced a competition to promote all-sung English opera. The theme, which used a text by no less a playwright than William Congreve, was "The Judgment of Paris". Four composers accepted the challenge: younger brother of Henry Purcell, Daniel; John Weldon; Gottfried Finger and John Eccles. Their versions were all performed in the spring of the next year – Eccles' on March 21st (1701). It did not win (despite being expected to); but was placed second to Weldon's, with Purcell's third. Whether as a result of this disappointment or not, Eccles soon ceased to write and retired to "private life"; this possibly deprived us of a talent, if not so great as that of Purcell's, nevertheless worthy of being considered a successor to the recently-dead composer.

In terms of musical idiom John Eccles (c.1668-1735) is from the generation immediately following Purcell. In places (in chorus movements like O How Glorious [tr.18], for example) the impact and scale are very Handelian. Yet in almost the next number (Stay, lovely Youth [tr.20]) the tonality and chromaticism could almost be Purcell's.

At barely three quarters of an hour The Judgment of Paris is not a long work. On this delightful CD it's supplemented by three even more Purcellian Mad Songs sung by the three female protagonists in the opera. It's a clean and straightforward piece devoid of italianate flourishes or spurious devices. It well reflects the rhythms of English speech in ways in which Henry Purcell's vocal music does. Not without sophistication and moments of dramatic tension, the score is easy to listen to; it makes an undiluted impact on the listener even half-familiar with the conventions of the genre. The associations of character and instrumental color (trumpets for noble and ceremonial entrances, for example) work well; there is much contrast between these and the more intimate passages, when clarity and closeness of singing allow character and circumstance to emerge fully.

The standard of playing and singing on this superbly-engineered Chaconne CD is high. There is a focus, a dedication to purpose, as well as a real sense of justified enjoyment that easily eclipse any tendency to treat the work as an oddity or to play up any curiosity value that it may have accrued in our time. The five principals are supported by the Orchestra and Chorus of the Early Opera Company with about 20 and 12 performers respectively. The presence and contribution of these forces are always appropriate to the scale of Eccles' conception: no bombast or gilt. Something of a chamber opera feel to the setting – almost in the ways Benjamin Britten so favored nearly three centuries later – amplifies the intensity of the work, which centers around the Greek mythological contest that led to the Trojan War.

Tempi, attack and phrasing all take Eccles' setting at face value with no attempt to "update" it or make it "relevant" given the idiom and subject matter perhaps alien to our ears when coupled with the context of a dramatic competition. In the excellent and expansive liner notes the choice of instruments is explained: equal tension, pure gut (except in the lowest bass sections) stringing was chosen, with bass violin not double bass. A is 392Hz; the result is a warmer, richer, mellower less "piping" or fruity sound than we sometimes hear in such pieces. Eccles' "The Judgment of Paris" doesn't need to be shored up when listened to carefully; but the arrangement of sounds and instruments employed here certainly confers some extra weight on it.

This is undeniably out-of-the-way repertoire. It starts by being inevitably taken as of secondary (maybe even circumstantial) significance and quality when compared with Purcell, Locke and Handel, say. But the Early Opera Company under the meticulous and inspired Christian Curnyn has produced a persuasive and stylish CD which ought to appeal to lovers of the music of Purcell's time. And – thanks to the clarity, unhurried and somewhat low key nature of their performing approach, which nevertheless loses no impact – to a wider audience still.

Copyright © 2010, Mark Sealey.