The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- W.F. Bach Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

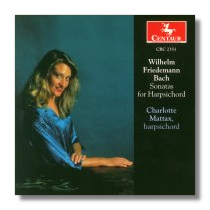

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

Sonatas for Harpsichord

- Sonata in G Major, F. 7

- Sonata in A Major, F. 8

- Sonata in D Major, F. 3

- Sonata in B Flat Major, F. 9

- Sonata in E Major, F. 5

- Sonata in C Major, F. 2

Charlotte Mattax, harpsichord

Centaur CRC2351

Wouldn't it be nice if Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710-1784) were recognized for who he is – an original, creative figure with his own considerable merits, and not just "one of J.S. Bach's sons", or "his oldest son"? Here's a CD of otherwise broadly neglected keyboard sonatas (only Robert Hill's Naxos series, of which we have but the first volume on 8557966 is comparable) played with great style and commitment by Charlotte Mattax on a modern (1994) harpsichord by Willard Martin after an original by Nicolas Blanchet from about 1720.

To be fair, it doesn't help matters that Sebastian himself openly regarded Wilhelm Friedemann as his inheritor. Nor that the latter's own public musical career was in many ways highly unsatisfactory: he never got what he wanted from his employers in Hallé, for example; and spent the last decade of his life in poverty and retreat (in Berlin) clearly considering himself still to be under his father's mighty shadow… he felt obliged both to claim some of the Sebastian's work as his own and tried to pass off at least one work of his own as his Sebastian's.

Yet there is barely a note of self-pity in the music we hear on this CD. There is certainly melancholy, and resignation – in the weary Grazioso [tr.11] of the B Flat Major, F9, surely, for instance. That he was an outstanding keyboard virtuoso makes it more than probable that some of his most expressive music should be written for the harpsichord. Indeed, the early D Major, F3, [tr.s 7-9] was a publishing failure because it was considered unplayable.

Not that Mattax overplays the at times almost spectacular nature of the music. Indeed, her measured yet colorful touch tackles nicely the musical confluence of late Baroque, elegant, Italianate and Empfindsamer styles. Although the format of these pieces is fast-slow-fast, there is immense variety in melody, harmony and even structure within (as well as across) the movement(s). One is reminded of Haydn at times, by the sweetness and drive; of J.S. Bach by the counterpoint; of Scarlatti by the conjuring up of mood by variations in tempi; and even of Mozart (in the Grave of the C Major, F3 [tr.17], for example) by the plangent tonality.

The music often twists and turns like a stream breaking its banks – and (almost) regretting it. And Mattax enters into the water without forgetting what's on land. She interprets such developments as Friedemann's exercising a just freedom, rather than caprice. But by achieving just the right balance between detachment – standing back from – and involvement – absorption in – this aspect of the spirit of the composer's musical invention, and allowing a stern but relaxed grasp of his structures to inform her playing throughout, she truly goes quite a way towards making the case for a greater understanding of his musical world. Then she supplies many a pointer to that appreciation. Tunefulness, pulse and textures that at times sound richer than they can be on a solo harpsichord all contribute to our taking a real delight in Friedemann's music for what it is.

There is an informative essay in the booklet accompanying this CD. Its acoustic is clear and close. If you don't know the repertoire or want to be delighted and stimulated by original music, confident of its own power to affect and surprise, expertly played by a sympathetic musician fully aware of the challenges of properly contextualizing the music of this under-rated composer – especially, able to distinguish him from other (Bach)s of his generation, this CD can be commended.

Copyright © 2010, Mark Sealey.