The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Corigliano Reviews

Harbison Reviews

Hersch Reviews

Kernis Reviews

Kolb Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Sousa Updated

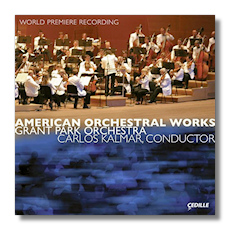

American Orchestral Works

- Barbara Kolb: All in Good Time (1994)

- Aaron Jay Kernis: Sarabanda in Memoriam (1997/2003)

- Michael Hersch: Ashes of Memory (1999)

- John Corigliano: Midsummer Fanfare (2004)

- John Harbison: Partita for Orchestra (2000)

Grant Park Orchestra/Carlos Kalmar

Cedille Records CDR90000090 76:00

Summary for the Busy Executive: Middle America.

This CD brings together recent works by American composers, both better- and less-known, from the conservative side of things. No boops and squeaks, no rhythmic sludge, no plug-ins. Like most such collections, some pieces come off better than others. Without a Genuine Masterpiece Detector, I can't tell you which of these scores will live for the ages, but that's never the point of music, or any art, for me. Probably the least spiritual person you will ever meet, I want music to either stimulate my mind or stir my hormones. Most of these works pass that test. In a way, the program reminded me of those of the Sousa band in the early part of the last century, which mixed serious classics, pops, and lollipops. All I seemed to need was a bucket of fried chicken and a tub of potato salad.

You can get the gist of Barbara Kolb's exciting curtain-raiser, All in Good Time, through the title. This piece concentrates on rhythm. From vigorous opening, somewhat reminiscent of Walter Piston, the work winds down to its opposite, an evocation of near-stasis. From there it builds back up. Kolb largely ignores harmony and melody – indeed, the end is mainly the repetition of one note – but manages to pull off an exciting work. My reservation comes down to the performance. Kalmar seems to run out of dynamic room and therefore gives you a crude, hammering close, rather than an ever-increasing build.

I've never cared for Corigliano's music, and the Midsummer Fanfare doesn't win me to his side. In fact, it seems a compendium of his worst habits. There's the "parting the mists of time" opening one encounters in many others of his works, which so often sound as if somebody paid him by minutes produced. In this case, the noodling around (because that's what it is) lasts for slightly more than half the piece. When the work finally gets around to chewing its thematic meat, Corigliano makes very little of it, despite an arresting idea, as if he gums his food. Why does he get commissions?

If the Corigliano comes down to trendy padding, Michael Hersch's Ashes of Memory diffuses a lot of good ideas and thus dulls the effect. In two movements, the work lays out its basic material in the first movement. I'm sure that if I were to look at the score, I'd find a standard motific development. But music is ultimately a matter of the ear, rather than the eye. On the rhetorical level, the piece proceeds as "one thing and then another." The far more successful second movement moves more purposefully, but somewhere into the middle there's a restatement of part of the first-movement exposition for no reason I can come up with. Still, I prefer this to Corigliano.

I haven't yet made up my mind about the Kernis Sarabanda. For some reason, I have trouble making my way through it. Yet I recognize its superb craft and its gorgeous string sonorities. At times, I think I'm listening to one of the great slow movements since Beethoven; at others, I'm asleep. The fault may lie in the monochromatic performance. Kernis dedicated the piece to the victims of 9/11 but had conceived it as part of his string quartet years before. He arranged that movement for string orchestra and hence the new title and dedication. Perhaps the piece not laboring under the burden of expectations for a suitable In Memoriam of something so far beyond the merely tragic exorcises the curse of pretention or presumption. Like Bruckner, Kernis dares profundity. You can't accuse him of sloughing off. I'm just not sure how close he comes. At any rate, it's something I'll have to listen to several more times.

Right now, I like the Harbison Partita best, but in a way, this little concerto for orchestra strikes me as the routine well-written piece I hate to review. There's nothing wrong with it, but neither does it contain any real risk, as I find in the Kernis. I may worry that Kernis's risk might not pay off, but at least he took it. The Harbison more or less updates neoclassicism with a slightly expressionist idiom. It reminds me a bit of the Sessions Concertino for Chamber Orchestra, but without that score's authority. Of its four movements, I like the second – a fleet rondo – best. However, it also moves the most convincingly of any work here. Harbison comes up with original, successful narrative strategies, pretty much free of contemporary cliché. But everything stays at a certain level, just below boiling. Nothing reaches out and grabs you. The pleasures of the piece come at you from a certain remove. The music doesn't really change you, as even great light music (the Fledermaus overture, for example) does.

The Grant Park Orchestra under Kalmar presents these works in a highly professional way and standards of playing have risen quite a bit in my lifetime. Nevertheless, they don't reach the level of revelatory or even vulgar enthusiasm. To me, the disc is a curiosity. How much interest do you have in contemporary American music?

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz