The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Perkinson Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

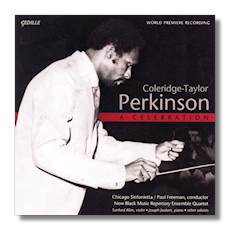

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson

High Modernist

- Sinfonietta #1 for Strings (1954-55)

- Grass (1956)

- Quartet #1 based on "Calvary" (1956)

- Blue/s Forms for Solo Violin (1972)

- Lamentations: Black/Folk Song Suite for Solo Cello (1973)

- Louisiana Blues Strut (A Cakewalk) (2001)

- Movement for String Trio (2004)

Joseph Joubert, piano

New Black Music Repertory Ensemble Quartet

Sanford Allen, violin

Tahirah Whittington, cello

Ashley Horne, violin

Jesse Levine, viola

Carter Brey, cello

Chicago Sinfonietta/Paul Freeman

Cedille Records CDR90000087 79:00

Summary for the Busy Executive: Strong, beautiful music.

This CD has brought home how much we in the United States view life through the lens of race, even with those areas not normally considered racial. Not only do we have Black Music (and, by implication, White Music), but we tend to attach moral judgments to those artists who "cross the line." Critics assail Gershwin's music as parasitical of Black Music. Fletcher Henderson gets accused of, essentially, "Tom-ing" in his work of the early Twenties. Behind all this lies a conception of Authentic Black Music: improvisatory, syncopated, based on dance and African forms, ecstatic rather than "intellectual," and, in some quarters at least, created only by Blacks. Accept no substitutes. And yet … for more than a quarter century, I lived in New Orleans, where musicians of various ethnicities learned from one another. Louis Prima grew up a couple of blocks away from Louis Armstrong. New Orleans musicians never rigidly categorized music. To hear them talk, it was all "The Music." Furthermore, you would have insulted them by insisting that they shouldn't be playing Bach or Ravel. It's part of the larger question of Black Identity – not only What is Black, but Who is Black. As a weak-tea Jew, I have some personal experience with a similar phenomenon, which I call the Aunt Retta Syndrome. My Aunt Retta, a lovely woman who grew up early in the twentieth century, believed not only that Jews did only great things, but that all great things were done by Jews. It's a "circle the wagons" mentality.

On the other hand, certain artists don't want to bother lugging around this extra baggage. They feel the duty of artists to express themselves in ways true to their own experience and not necessarily to others' idea of what that experience should be. After all, it's hard enough to create without having someone – often without technical knowledge of your art – telling you that you're doing it wrong.

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson (1932-2004) studied composition with, among others, Vittorio Giannini. He made his living arranging and "musical directing" for the likes of Belafonte, Lena Horne, Marvin Gaye, and Max Roach. Indeed, he played piano in several of Roach's small groups. He had, therefore, fairly solid jazz and soul credentials. However, his concert works – at least the ones here (the only ones I know) – have nothing specific to do with jazz, for which some Authenticists came down on him. Perkinson wrote at least two graceful demurrals: I cannot define black music. I could say that it is a music that has its genesis in the black psyche or the black social life, but it is very difficult to say what black music really is. There are kinds of black music, just as there are kinds of other musics. [the only black aspect of my music is inspiration. … Only you can decide if the life you live is significantly black; no one can decide that for you, and I don't think it's right for anyone to pass judgment on the nature of your involvement.

In other words, let me compose as I have to compose.

The musical equivalent of writers like Ralph Ellison, Robert Hayden, and Melvin B. Tolson, Perkinson in these pieces is more High Modernist than Vernacular Black, but his inspiration often comes from Black life, possibly (and this is a radical notion) because he lived his own version of that life. All of these people have occasionally been pulled over by the Culture Police, so these shopworn ideas still circulate.

The Modernism comes out immediately in the earliest piece here, the Sinfonietta #1. The composer that comes to mind most readily isn't Giannini, Perkinson's teacher, but Hindemith – the granitic harmonies, the counterpoint that intensifies rhythm. Yet Hindemith lurks in the background, because something individual goes on here as well. You don't mistake Perkinson for Hindemith. That individuality comes out in livelier rhythm. Think Hindemith Meets Bartók, and you'll get the idea.

The rhythms stamp even more strongly in Grass, a Konzertstück for piano, strings, and percussion inspired both by Sandburg's poem and by Perkinson's military service in Korea. You see it more clearly when you say what it's not. It neither tells a story nor mickey-mouses the poem. In A-B-A structure, the work uses only one idea: vigorously, then with a weird lack of affect, then even more vigorously. The free-verse poem tells of the slaughter of war and of the eerie stillness of former battlefields, with a refrain of the grass as healer of earth's scars. Standing sturdily on its own, the music strongly abstracts these emotions. If you didn't know about Sandburg or Korea, you wouldn't have guessed.

The string quartet strikes me as warmer than the preceding pieces. The spiritual "Calvary" ("Every time I think about Jesus, Surely he died on Calvary") clearly provides the material for the first movement. However, the spiritual becomes more and more abstract as the movements progress. In the second movement, we get mainly the rhythms from the opening strain. The rondo finale uses the song, but only in the episodes. The rondo subject's affinity with the spiritual comes out only as the movement approaches its end. The entire quartet is beautifully made.

The three solo pieces – Blue/s Forms and Louisiana Blues Strut for violin and Lamentations for cello – immediately acknowledge the Bach solo string pieces as their ancestors. Perkinson emphasizes counterpoint and conceives of the music in two, three, and at times even four parts. Although the violin piece celebrates and comments on the blues, there's no real blues in it. The second movement in particular – slow and free – evokes more the blues singer than the blues. Lamentations, in the words of the composer, "is the reflection and statement of a people's crying out." I grant Perkinson his inspiration, but I don't really hear it. I'm too impressed with the contrapuntal tricks. The composer subtitled Lamentations with "Black/Folk Song Suite." Although he takes off from folk forms ("Fuguing Tune" is the first movement, for example; "Calvary Ostinato" is the third), the music moves so far away from the folk that in the finale Perkinson could quote from Stravinsky's Le Sacre without a jar. In the "Calvary Ostinato," the spiritual gets sliced and diced even more than in the quartet and set against a repeating bass line. Louisiana Blues Strut keeps closer to the spirit of the cakewalk, but really bears the same relation to the folk form as a Bartók workup of, say, a czardas. Perkinson here (as opposed to every other piece on the CD) swings like blazes.

From Perkinson's deathbed comes the Movement for String Trio, a slow, melancholy Bach-like aria. Even if you didn't know its circumstance of composition, you'd sense the composer's great emotional involvement. For me, it ends a little too soon. I wish he'd had the time to spin it out longer, but even so it testifies to a fine musical spirit.

The performers range from acceptable to very good. Paul Freeman and the Chicago Sinfonietta do okay, but you can easily imagine a better performance. Pianist John Joubert provides most of the excitement in Grass. For a first recording, the New Black Music Repertory Ensemble Quartet champion the string quartet enough to allow you to see its stature. I hope other quartets, or even the NBMREQ with more experience, take it up. The outstanding readings come from the soloists. Sanford Allen makes a difficult score cohere. Tahira Whittington brings excitement to the cello suite, but I wished for tighter control. The string trio – Allen, Jesse Levine, Carter Brey – imbue Perkinson's swan song with depth and beauty. Violinist Ashley Horne comes off best with a jazzy reading of the Louisiana Blues Strut that shows you not only the sophistication of the piece, but the fun of it.

I contend that the music here transcends rigid categories. I recommend it not as an appeal to specialists or as an exhibit in a narrow sociological context, but for its own powerful sake.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz