The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Yardumian Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

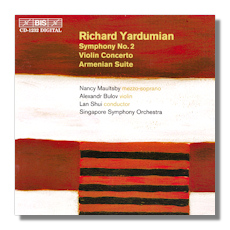

Richard Yardumian

Orchestral Music

- Violin Concerto (1949, rev. 1960/1985)

- Symphony #2 "Psalms" (1949, rev. 1964)*

- Armenian Suite (1937, rev. 1954)

Alexandr Bulov, violin

Nancy Maultsby, mezzo soprano

Singapore Symphony Orchestra/Lan Shui

BIS CD-1232 66:25

Summary for the Busy Executive: Psalmist from Philly.

Born, grown up, and dead in the environs of Philadelphia, Richard Yardumian buckled down to composition relatively late, in his twenties, encouraged by figures like Stokowski and Iturbi. He had very few contacts in the places it would have done him the most good, like New York or London. His music got disseminated mainly through recording, almost exclusively by Ormandy and the Philadelphia and later, Anshel Brusilow, Ormandy's former concertmaster. Yardumian also picked up the advocacy of John Ogdon and Gerald Abraham. Unfortunately, he remains a somewhat of a cult figure, out of joint with his time, something that probably bothered him.

His music, dissonant although modal, religious in inspiration, ran counter to the anti-religious, pro-technical sentiments of the musically influential. More than once, he called Bach his favorite composer, and when he discussed music, it was usually in terms of analogies to the cosmos. He also had the misfortune to create his own dodecaphonic system, generated by the alternation of major and minor (or minor and major) thirds up and down the piano keys – in other words, something very close to the octatonic scale, and thus tonally based. I remember one writer (probably British, but after so many decades, I'm not sure) who threw a fit over this. "How DARE he?" the critic thundered, as if Yardumian had done so for the sole purpose of supplanting Schoenberg, and thus the reviewer missed the point of any system, which is not the system itself, but what it allows the composer to create.

Yardumian's music exhibits a certain roughness, awkwardness even. You can't him imagine writing something like Stravinsky's "Dumbarton Oaks" Concerto or Ravel's Introduction and Allegro. He created only a very slim catalogue, and he often took years to get a piece into its final form – true of every work on this program. However, he has a very high proportion of winners. At his frequent best, he achieves a beautiful nobility of expression, sometimes epic, sometimes meditative, similar to Ernest Bloch, although you can easily differentiate between the two.

The Armenian Suite, the earliest piece on the program, shows Yardumian's initial influences, mainly Prokofiev, Bloch, and, surprisingly, Rimsky-Korsakov. It began as a single piano piece and grew to an orchestrated, multi-movement suite. Ormandy asked for a new ending, thinking that Yardumian's original, though fine as a movement in itself, lacked the necessary "wow" factor for a finale, and Yardumian obliged. The movements – songs and dances – take either traditional Armenian tunes or Armenian-inspired ones original with Yardumian. The fast movements in general use bright sonorities, the slow movements more muted ones.

The violin concerto originally consisted of the first movement only. A second movement appeared in 1960. At Ormandy's insistence, Yardumian also added a fast finale, and Ormandy recorded this version with Brusilow as soloist. The problem was that the finale, though full of interesting ideas, was over in the blink of an eye. It seemed tacked on. Yardumian revised the finale yet again, expanding it, teasing out the implications of its themes. I consider it now one of the great American violin concerti.

In 1947, Yardumian wrote a setting for tenor and orchestra of Psalm 130, De Profundis, which Ormandy and the Philadelphia recorded. Years later, Ormandy asked for a symphony as well something for contralto Lili Chookasian, with whom he wanted to work. Yardumian rewrote his De Profundis and added a second movement, nearly twice as long as the first, with more psalms for texts. Chookasian was that rare commodity, a true contralto, rather than a mezzo with low notes, and this seemed to have inspired the composer, who came up with a part that exploited her huge range and rich vocal color. The symphony, however, can impress a listener as extremely loose. Not only does it threaten to break down into individual psalms, it's hard for performers to find the structural thread and keep it going. Much of the work's coherence depends not only on the conductor, but on the soloist, who has a huge solo cadenza made up of the work's principal ideas. But even in a loose performance, the power of the symphony comes across. To me, there's nothing else like it, either in structure or in mood. Yardumian takes huge risks, and they pay off. What we get is the voice of the Psalmist.

All the music on this CD has received other recordings. Recordings exist somewhere of Ormandy and the Philadelphia doing not only the Armenian Suite and the Symphony, but the original Psalm 130 and the Armenian Suite. Chookasian, the Utah Symphony, and Varujan Kojian recorded the symphony, as well as the Armenian Suite (see my review). It's time for recording companies to move on through Yardumian's catalogue and give us the Symphony #1, Cantus animae et cordis, Missa "Come, Creator Spirit," the Chorale Prelude, and his masterpiece The Story of Abraham, an oratorio that sums up and crowns the composer's artistic achievement.

Frankly, I saw the words "Singapore Symphony Orchestra," and my heart sank as I conjured up the Firesign Theater's "Musical Heritage Surplus Club of Hong Kong" – a quick route to a quick buck or, more likely, the last resort of an enthusiast with not-enough money to get the music recorded by anybody decent. Boy, was I wrong! I admit my mistake. These readings overall are the best I've heard, surpassing even an old hand like Ormandy, which is saying something. The playing is crisp, the sonics clear. Of the three recordings of the symphony I've heard, this reading coheres most without sacrificing any of the score's considerable drama. Lan Shui may let you see the Legos that Yardumian manipulates, but he also builds a compelling narrative. Mezzo Nancy Maultsby hasn't Chookasian's monumental vocal quality and she has occasional intonation skews. Since she sings all by herself a lot of the time, this could cause problems when the orchestra enters, but she's never far enough out to make you cringe. It's an incredibly difficult part. Chookasian mastered it over the years. Maultsby does a fine, credible job, nevertheless. The Armenian Suite throws off sparks. The Violin Concerto is the only CD recording of this work and the only recording of the final version. Simply on the level of performance, it compares well to Brusilow and Ormandy, although Brusilow plays with more blood than Bulov does. On the other hand, Bulov plays cleaner. It's not really a matter of preferring one over the other but of appreciating two fine accounts.

Copyright © 2009, Steve Schwartz