The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

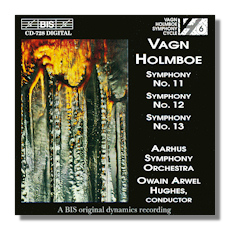

Vagn Holmboe

Last Symphonies

- Symphony #11, Op. 144 (1980)

- Symphony #12, Op. 175 (1988)

- Symphony #13, Op. 192 (1994)

Aarhus Symphony Orchestra/Owain Arwel Hughes

BIS CD-728

Summary for the Busy Executive: Glowing performances of a neglected master.

Locality seems to matter to a composer's acceptance. It strikes me that composers without ready access to New York, London, Paris, Berlin, Milan (for opera composers), Vienna, Prague, and St. Petersburg find themselves cast in the Outer Darkness. Very few took Elgar seriously as long as performances of his work confined themselves to the north of England. I doubt many of us could name a Ukrainian or Croatian composer, or a Rumanian composer other than Enescu, who made his reputation in Paris. For decades after his death, Nielsen – one of the finest symphonists of this century – had the reputation of a local wonder. It took conductors (like Horenstein) mainly with peripatetic careers to reveal Nielsen as the mighty European figure he always had been. Horenstein himself once pointed out that the first translation into English of the writings of 19th-century Danish philosopher and theologian Kierkegaard appeared in the 1940s, after which he became part of any self-respecting intellectual's toolkit – yet another example of locality impeding recognition.

The Danish symphonist Vagn Holmboe has been stuck with the label of Nielsen's Successor, at least in his own country. His music never really penetrated to the large centers of classical music until close to the end of his life, due to some extent both to the Danish recorder virtuoso Michala Petri, for whom he wrote a trio and a concerto, and to the BIS label's decision to record a symphony series. The works here represent Holmboe's final examples of the genre.

As far as I can tell, the only things that link Holmboe and Nielsen are country of origin and a symphonic cycle. I don't find one's music itself all that similar to the other's, except possibly in general artistic aim – an Apollonian emotional distance and emphasis on form, rhythmic vigor, textural clarity, and a handsome, streamlined, "cool" sound for the orchestra. But this describes more than one composer. If you asked me, I would say the composer I find closest to Holmboe is Hindemith or perhaps the American Peter Mennin.

Born in 1909, Holmboe entered the Royal Danish Music Conservatory at the age of 17, on the recommendation of Carl Nielsen. He never studied with Nielsen, however. Instead, after graduation, he went to Berlin and studied with Ernst Toch. Yet, Toch's chromaticism doesn't touch him as much as Hindemith's quartal harmonies do. Perhaps he got from Toch his concern for architectural clarity, reflected, I believe, in the emphasis on chamber music and on music for chamber ensemble in his output. Toch's considerable achievement as a composer has yet to win recognition, even among modern-music fans. His success as a teacher lies even further in obscurity. He had the happy ability to say useful things to a budding composer without imposing a specific system or set of procedures, thus allowing his students to find their own voices. Not one of Toch's pupil's sound like Toch, and few sound like each other.

Holmboe's music is firmly modern, but you don't lose your way in it – a considerable achievement, since his larger structures tend to idiosyncrasy. The musical intent is almost always apparent, as is the relation among the constituent parts of a work. His breakthrough piece, the Symphony #2, established him as Denmark's leading living symphonist, which – our loss – got him only as far as Copenhagen. Even now, much of his music – slightly under half – lies unperformed (Holmboe died in 1996). I knew earliest one of his string quartets (the 8th), which I got about 25 years ago, as a bonus on the flip side of a Nielsen string quartet. I wish I could say that Holmboe's quality declared itself to me immediately. I remember mainly my annoyance that it didn't sound anything like Nielsen. Even now I can't recall exactly what piece turned me on to Holmboe, and at this point I can't believe I was so deaf. I feel like the person who's discovered for himself that Beethoven is, after all, really very good.

The symphonies recorded here crown a lifetime's work. All show a remarkable psychic equilibrium – a satisfying emotional balance. If you think that great music has to reflect a tortured psyche, these works aren't for you. They're not necessarily placid – a lot happens in them – any more than the music of Bach or late Brahms. I suppose an even closer analogy might be the finale of Mozart's "Jupiter": the same emphasis on counterpoint and the same combination of authorial power and detachment. These works don't celebrate the sorrows or joys of an individual; they don't confess anything. They are dramatic in the classic sense: that is, they look outward, to understand not through the personal, but through the unfamiliar. This view probably doesn't coincide with our Romantic and Freudian notions of proper art, but I think Bach, Handel, and Haydn would have understood it pretty well.

Holmboe builds the symphonies in roughly the same way. In fact, it's the classical method of a small number of cells, combined and varied to grow an entire symphony. Symphony #11 begins with a Hindemithian theme of successive fourths on the flute and continues with a heavy-footed rhythmic motive made up of two 4/4 measures divided into 3+3+2+2+3+3 – a mirror symmetry. The rhythmic motive and submotives associated with it (including ideas that flirt with the "Dies irae" chant) dominate the opening part of the first movement and generate most of the kinetic power, although the quartal theme is never out of the picture for very long. Although Beethoven would have recognized the procedures, the form of the movement is something else again – a long crescendo building up to a great climax, intensified by increasing contrapuntal complexity. The bubble bursts to, surprisingly enough, nothing – a long pause. Holmboe starts up again with a perky quasi-fugue as coda. Given what's gone on before – and it uses the same motives as the crescendo in a downright merry way – it comes over as a smile at the solemnity of the movement. The rhythmic motive tries to stir things up again, but it's cut off by the solo flute, ending the movement on a thread of sound. The second movement combines features of slow movement and scherzo, featuring mainly variants of the quartal motive, broken up by transformations of the heavy-footed rhythmic idea. In fact, after setting up the listener to expect a quiet (though uneasy) movement, Holmboe interrupts with a blast from the first and ends as you would have expected the first. The "Dies irae" sounds out loud and clear as the movement blares to an abrupt close.

The magnificent third movement sums things up, but not neatly, and provides a key to the musical drama – a conflict between the two main motives. In many ways, it represents the opposite of the first movement, in that this time the quartal theme focuses the music's energy. The finale ends, again abruptly, with a soft leave-taking by quartal theme. All this happens in a stunningly beautiful contrapuntal framework. To make the counterpoint apparent, Holmboe has to create an orchestration clear as water. Especially impressive are the writing for massed horns and the lively, though not overpowering handling of the percussion, particularly the tuned percussion. The mysteries of the work remain, however, chiefly in what to make of the endings, other than Holmboe doesn't like to draw things out. It's as if the universe has suddenly disappeared on you and you're left with weird little traces – a distant car horn or the echoes of a ticking clock.

Symphony #12 throws certain features of Holmboe's musical language into relief – above all, the emphasis on intervals and on counterpoint in his musical thinking. The composer Stefan Wolpe once half-jokingly remarked to a student that "fugue is what you do when you run out of ideas" – more than a grain of truth to that. That is, a fugue can be seen as an easy way to momentarily grab the listener's attention, without really advancing the musical argument, and it's a danger that the contrapuntal composer most obviously risks. For Holmboe, counterpoint doesn't necessarily mean contrapuntal forms like fugue, but simultaneous planes of musical activity, development, and thought. In other words, it advances the musical matter like crazy in different directions at once. Yet everything remains clear. The main motive – G F# C G – emphasizes the half-step (G-F#), the tritone (F#-C), and the fifth (C-G), but the sound of the tritone seems to dominate the symphony. As a result, the music takes on a less stable, less massive emotional tone than the eleventh. A sense of unease pervades the first two movements. The finale seems to sweep away the funk under its con brio, but the anxiety persists. Simple merriment won't do here, and the bustle turns resolute and grim, finally dispelling the gloom in three very powerful final chords. One bit of amazement: the symphony, longer than its predecessor, actually feels more compact and to the point.

Holmboe wrote his 13th at Owain Hughes's request, in gratitude for undertaking the recording project of the complete symphonies. In failing health, Holmboe knew this symphony would likely be his last, but he completed it in 1994. One might expect some grand summing up or extended leave-taking, but Holmboe avoids the obvious. The symphony gets right down to business with a powerful rhythmic motive and, again, amazingly efficient percussion writing. I can pay no greater tribute to Holmboe's use of percussion than to say I'm not aware primarily of percussion but of a force or brightness in the music. The main motive is a heavily chromatic one, which in one of its transformation becomes the B-A-C-H theme (Bb-A-C-B) – appropriate for a contrapuntal composer. Again, the counterpoint isn't a matter of choosing the conventional forms, but of developing different material on simultaneous and distinct sonic planes. It fits together beautifully, like the click of the lid on a well-made box. Once more, the same musical material pervades all three movements. Once again, the movements lose all their considerable energy all of a sudden and end with either a stamp of the foot or in the middle of something important with a quick, "Oh, well." We have grown accustomed to mighty coda or the lingering long good-bye. Holmboe says what he has to say and stops – so it's a trifle unsettling. The symphonic argument again is concentrated, powerful, and compact. No sense of detour or ramble here.

Who knows from the Aarhus Symphony Orchestra? On the basis of the Holmboe series of recordings for BIS, I'd consider them as good as, say, St. Louis and better than many U.S. orchestras with larger reputations. Hughes leads handsome performances of handsome and, I think, significant works. Holmboe's intricate counterpoint remains clear, and the sound is full and warm. I've never heard a Holmboe piece without the highest level of craft and a good deal of poetry besides. To me, another major modern figure waits general discovery.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz