The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

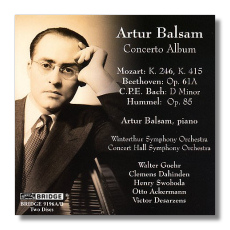

Artur Balsam

Concerto Album

- Wolfgang Mozart:

- Piano Concerto #8 1

- Piano Concerto #13 2

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto in D Major, Op. 61A 3

- Johann Nepomuk Hummel: Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 85 4

- Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: Piano Concerto in D minor, H.427 [Wq23] 5

Artur Balsam, piano

1 Winterthur Symphony Orchestra/Walter Goehr

2 Concert Hall Symphony Orchestra/Henry Swoboda

3 Winterthur Symphony Orchestra/Clemens Dahinden

4 Winterthur Symphony Orchestra/Otto Ackermann

5 Winterthur Symphony Orchestra/Victor Desarzens

Bridge 9196A/B AAD monaural 2CDs: 65:24, 75:52

Pianist Gerald Moore sometimes was referred to as "The Unashamed Accompanist." On LPs and on concert stages, he partnered some of the greatest singers of his time, including Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, and he was like a fresh herb in a fine bowl of soup: although he did not call attention to himself, he was an essential ingredient not to be eliminated or even substituted. He had no inferiority complex about what he was doing, perhaps because he did it so well.

Like Moore, Artur Balsam apparently did not have much of an ego. He could have had a stellar solo career, but he seemed quite contented to be a chamber musician primarily, and to partner musicians such as Yehudi Menuhin and Nathan Milstein. With Beethoven's or Mozart's violin sonatas, for example, one common way to rankle pianists is to suggest that they are accompanying the violinist in these works. (Indeed, the two musicians must be equal partners in this repertoire.) One senses that Balsam took such unintentional slights in stride and then got back to doing what he loved and what he did best: making music.

This is not to suggest that Balsam never appeared in the spotlight. He recorded most of Mozart's piano music, for example. During the 1950s, he made many recordings for the Concert Hall label, usually of out-of-the-way repertoire, and five of his concerto recordings have been assembled here by Bridge. This is a nice tip of the hat, on the part of Bridge, because Balsam already appears on the label in numerous live recordings from the Library of Congress with Milstein, the Budapest String Quartet, and other musicians.

Bridge's release comes with extensive booklet notes by Dan Berlinghoff, who studied with Balsam in the 1980s, and who was director of the Artur Balsam Foundation for Chamber Music for ten years. Seventeen pages of the booklet are devoted to a biography of the pianist, who was born in the Polish city ofºodz in 1906, tracing the career's ascent, and his contributions to not only solo and chamber music, but to pedagogy, and also the promotion of under-represented repertoire.

Back in the 1950s, the five concertos presented on these two CDs were less familiar than they are today. One could not go to the shelf and take down several complete sets of Mozart's piano concertos, for example. Labels such as Concert Hall (whose LPs were pressed on red vinyl!) filled a niche by giving collectors recordings of music that they could not find anywhere else. The performances were not glamorous, but they were noteworthy for their objectivity, and for their responsible treatment of the composer and of the repertoire. Modern ears might prick up in curiosity over the C.P.E. Bach, for example – Balsam plays a modern piano, but one can clearly hear a harpsichord plunking away in the depths of the Winterthur Symphony Orchestra – but inquiries into the "correct" way of playing such music hardly had begun in the early 1950s. And speaking of curiosity, the Beethoven concerto presented here is not one of the canonic five, but the composer's own arrangement ("reworking" might be a better word) of the famous Violin Concerto. The composer intended this as a present for the wife of his friend Stephan van Breuning. It has been recorded a few times since Balsam did so, but it remains a rarity compared to the version for violin and orchestra.

So what about Balsam? These recordings have a rare refinement, probably born of a lifetime of hearing other musicians play, while he did the same. He neither leads nor follows. This isn't playing that screams "look at me." Instead, it suggests, "Listen to us – we have something here you've probably never heard before." It's insinuating musicianship. In this era before "period performance" scholarship kicked into high gear, Balsam obviously was thinking about what performance style would present this repertoire to its best advantage. The result is playing in which extremes of tempo, dynamics, and expression are avoided. The key word is "balance." If a listener is not sympathetic to the repertoire, he or she might find these performances on the dull side, but I don't think these concertos need any "special help" – just the performers' intelligence and sensitivity. That is what they receive here. These recordings are a worthy souvenir, not just of an excellent pianist, but of early efforts to preserve byways of the repertoire and to bring them to a wider audience, just as certain specialty CD labels do today.

Unfortunately, Bridge has not included recording information, but perhaps dates, etc. Are no longer available. Although the sound shows its age – actual Concert Hall LPs seem to have been the source materials used – the transfers (by Adam Abeshouse and David Merrill) are very listenable.

Copyright © 2007, Raymond Tuttle