The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Carter Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

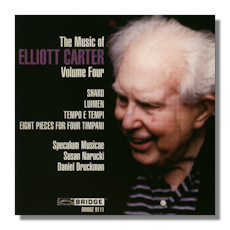

Elliott Carter

The Music Of Elliott Carter, Volume 4

- Luimen 1

- Shard 2

- Tempo e tempi 3

- Eight Pieces for Timpani 4

3 Susan Narucki, soprano

4 Daniel Druckman, timpani

2 David Starobin, guitar

1,3 Members of Speculum Musicae/William Purvis

Bridge BCD9111

This is volume four in Bridge's excellent and justly acclaimed series of the music of Elliott Carter, who will be 103 this December. It illustrates clearly two aspects of the composer's work that are crucial to understanding it: his love both of experimentation, and of process. Shard is a short (less than three minutes) piece for solo guitar (with David Starobin). It emphasizes the ways in which a reduced – apparently extracted and/or fragmentary – piece (one is reminded of Carter's other pieces implicitly or explicitly celebrating fragmentation) can nevertheless make a whole and self-standing musical statement.

It came to find its way, interestingly, into the longer Luimen, which is scored for the unlikely combination of trumpet, trombone, vibraphone, mandolin, harp and guitar. If proof were needed of Carter's supreme control of process in the course of experimentation, then not only that integration but also the rich and purposeful tapestry of those six instruments' sounds as well as the originality of differing tempi, melodic lines (almost competing at times, yet producing a compelling unity) and textures (equally challenging, surely; yet just as satisfying) provide such proof in Luimen. Both pieces exploit the subtle relationship between jagged (suggesting unfinished?) tempi and the nevertheless perhaps unexpected sense of completion which a figure of Carter's stature and experience can confer on even the most difficult situations, because of duration or instrumentation.

Not that Carter really sets himself such challenges for fun. There's always a thoroughly well-considered artistic purpose. In the case of Tempo e tempi, that is provided as much by the texts (by Montale, Quasimodo and Ungaretti) as anything else – although here too there is an emphasis on the organic growth that can (and should?) occur, when simple, single ideas are strong enough. Carter's attraction to these texts must have to do with his fascination with "competing" notions of time… tempi, rhythms, meters flow against one another; yet in so doing somehow create a whole that musically reflects the piece's title.

As in Luimen, the playing of Speculum Musicae is precise, focused, punchy and directed without loosing any of the music's (implied) sensuality. The only slight drawback is the somewhat stilted Italian enunciation of soprano, Susan Narucki; although her vocal endorsement of Carter's unification of text and successively different and often, again, challenging instrumental combinations with voice is total, the words – which are so crucial, and which she sings so clearly – would benefit from a singer more adept at the more delicate particularities of Italian pronunciation.

The longest work on this CD is the Eight Pieces for Timpani written not in the late 1990s, as were the other three, but as early as 1950 and revised, added to, until 16 years later. These two share the twin attributes of experimentation (in methods of the "metrical modulation" which is a hallmark of the composer) and selection, a strong sense of individual, extracted, validity… Carter prefers that no more than four of these pieces be performed in public at any one time. They make compelling listening and defy any preconception that a solo timpanist (here we have Daniel Druckman to thank and admire) cannot summon up a virtual world. Carter's use of tension and withholding of perhaps expected continuation of directions is only one of the processes used to maintain our involvement. Things for which many composers would not have used timpani. The same can be said for the appeal to vocalism which the pieces all make. Again, Druckman completely understands this and renders each piece with gentility and gentleness. In his attention to dynamic markings, for example, the sound of the four timps (including pedals) becomes more and more compelling and leads us to exactly where, one feels, Carter wants us to go in appreciating the relationship between extra-musical inspiration (the second piece, "Saë", for example explores natural ritual) and the pure technicalities of the production of sound on timpani over nearly 25 minutes. At the same time, the penultimate ("Adagio") moves into the most unusual areas of vibrato, glissando and harmonics – on timpani.

This is a CD which lovers of Carter's music in particular, and those eager to explore one of the world's still leading innovators in general cannot afford to miss. It's based implicitly on these two aspects of musicality: fragmentariness and an emphasis on the centrality of process to musical substance. And, to be fair, more can be got from the music if the listener is aware of that. The engineering and acoustics used are up to Bridge's usual high standards. The booklet is informative and helpful in providing historical background in particular; and the texts with English translations for Tempo e tempi. Bridge's "Music Of Elliott Carter" series is an exciting and important one. Don't miss out on this landmark volume if for no other reason than that the playing of those involved leaves you with a greater sense than ever of Carter's massive contribution to contemporary music – not because they "were there", or have merely "gone through the motions"; but because they truly understad the music, understand Carter, and understand how to make his unique contribution to music of our time as enjoyable, striking and transparent as possible.

Copyright © 2011, Mark Sealey.