The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Freitas Branco Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

From The Portuguese

Orchestral Works

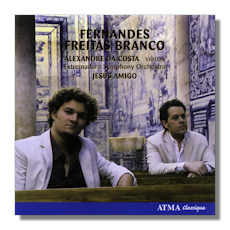

- Armando José Fernandes: Violin Concerto in E Major

- Luís de Freitas Branco: Symphony #2 in B Flat minor

Alexandre da Costa, violin

Extremadura Symphony Orchestra/Jesús Amigo

Atma Classique ACD2-2578 DDD 73:44

Summary for the Busy Executive: Comfort food.

Between the Renaissance composers Cardoso and Lôbo and the Modernist Braga Santos, I've heard very little classical music from Portugal. As far as I can tell, the ferment that seized Spanish music in the nineteenth century largely passed Portugal by. Spanish composers studied in France, Germany, and Italy and became intensely Spanish. Portuguese composers studied in the same conservatories and became French, German, and Italian knockoffs. The action in the twentieth century seemed largely to transfer to Brazil.

Armando José Fernandes took advanced study with Dukas, Boulanger, and Stravinsky, among others. Oddly enough, his violin concerto reminds me most strongly of Khachaturian's (1940). The first movement obsesses on an initial figure which generates all the other themes. Unfortunately, it's one of those pieces that steals from everybody and winds up sounding like nobody. There's a bit of Brazilian rhythm, a la Villa-Lôbos, some Creston-like harmonies, and some standard neoclassic turns of phrase, but I wonder where the composer is in all this. Despite the notes and the insistent rhythms, not all that much happens in this concerto. The various sections sound so much alike, due to the similarity of the thematic shapes, that it all seems to dissolve into a long drone. Interest picks up in the lively second-movement scherzo, which hops like a flea on a hot brick, although the transition to the trio – essentially, a full stop and a start – seems clumsy to me. I like the slow movement the best, a straightforward song whose main strain might relate to the generating idea of the first movement. Here, however, Fernandes contents himself with singing rather than with showing off his compositional smarts, and all for the better. Nevertheless, it results in something fundamentally pleasant, rather than heartbreakingly beautiful. The last movement, a rondo, totally misfires. It lacks the brio and fire of a concerto of that type. We return to the drone – a lot of notes and no significant activity. A concerto, of course, needn't end with a pyrotechnical display, but the Fernandes ends on nothing momentous or even on anything which gives a feeling of rounding things off or of summing up.

Born into a prominent musical family (his brother Pedro conducted the première of the Fernandes violin concerto – small world), Luís de Freitas Branco (1890-1955) studied in Berlin with Hansel und Gretel's Humperdinck. However, an encounter with Debussy sent him in a more progressive direction.

The second symphony comes from 1926. The composer wrote it on the occasion of his sister's entry into a Carmelite convent. Part of the plainchant "Tantum ergo" runs through the score.

Yet, with all of the wide-flung influences on Freitas Branco, the strong presence of César Franck surprised the hell out of me. The symphony opens with the chant, harmonized with Respighian archaism. We get to the main allegro, and suddenly it's 1888, with an agitated theme that would have fit nicely into Franck's d-minor symphony. A lyrical theme, related to the chant, is harmonized in a pure, Franckian chromaticism, and the composer recalls the chant theme at several points in the movement. The liner notes suggest a faith-vs.-doubt scenario, but to me the movement exemplifies a conflict between two adjacent musical eras.

The second-movement andantino comes straight out of the slow movement to the Franck symphony, but the composer writes well, if not with originality.

A scherzo follows. The main theme comes from the Tantum ergo chant, with the initial interval changed from whole to half step. This simple change gives the theme a new menace. The underlying bass rhythm comes directly from that of the second movement. Freitas Branco simply speeds it up. The liner notes try to make a case for the Modernism of this movement, but to me it sounds like a minor, though craftsmanlike follower of Liszt, with that same four-square clunkiness that sometimes afflicts even the master. Freitas Branco is aware of this problem, because he occasionally tries to break things up and obscure the main rhythmic pulse, just not often enough.

The finale, another sonata-allegro movement, kicks things off with an agitated theme derived from turning the chant upside-down. There's a lyrical theme as well, also fashioned from the upside-down chant. In addition, the chant itself makes its appearance in sections of chorale. The development is framed by two full orchestral unisons – the first on D, the latter on A-flat. I don't doubt that Freitas Branco put these in as feats of daring, but they don't in practice come off as bold or outrageous. After all, The Rite of Spring was over a decade old by this point. Again, this is a Nice Symphony, rather than an astonishing one.

The performers are okay. Violinist da Costa, a Canadian, has a small tone, although a true one. The orchestra plays with slight rhythmic problems, but it's awfully unfair to judge anybody on the basis of these works. Let's just say that nobody confounds your expectations.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz