The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Gardner Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

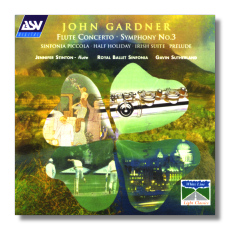

John Gardner

Orchestral Music

- Half Holiday – Overture, Op. 52 (1962)

- Flute Concerto, Op. 220 (1995)

- Symphony #3 in E minor, Op. 189 (1989)

- Prelude for Strings, Op. 148a (1978)

- Sinfonia Piccola for Strings, Op. 47 (1960)

- Irish Suite, Op. 231 (1996)

Jennifer Stinton, flute

Royal Ballet Sinfonia/Gavin Sutherland

Academy Sound & Vision CDWHL2125 62:46

Summary for the Busy Executive: Jack, be nimble!

English composer John Gardner (b. 1917) has flitted about the edge of recognition for years. Very few know who the hell he is, and yet some of his pieces have received many recordings and performances. Part of his problem, certainly, comes from his artistic outlook. He seems to regard himself as a craftsman, or even as a musical toymaker, rather than as an artistic titan. One can comfortably fit his idiom into the William Walton part of Sherwood Forest but his aims, generally speaking (the First and Third Symphonies are distinct exceptions), belong in a much more domestic neighborhood. He has conceived much of his music for amateurs, which, though it might sound easy on the ears, nevertheless springs little traps and tricks that keep performers' and audiences' minds nimble. The scoring is elegant and clean. After hearing a Gardner work, I tend to say to myself, "How neat!"

A distinct populist streak runs through Gardner's catalogue. Like Malcolm Arnold, he flirts with vernacular styles and jazzy (although not jazz) rhythms. Unlike Arnold, he avoids irony. The vernacular pleases him rather than serves to make a higher statement about the Nature of Art. He writes, essentially, light music, not as a holiday nor as a profession, but as an expression of something basic in his nature.

Almost all the works on the program share a modest viewpoint (the disc belongs to the "White Line Light Classics" series). Gardner wrote almost all of them for school or amateur orchestras. The brief Half Holiday counts as my favorite. It's bright, almost (but not really) cheap, and it wants nothing more than to bring a smile to your face. It works with two ideas, the second of which is simply the first flipped upside-down. The overture fairly bounces along, a little like the American Jerome Moross in its straightforward enthusiasm. Some Morossian harmonies as well.

The flute concerto, on the other hand, sings a bit more Romantically, a little like the Walton of the Second Symphony or the Cello Concerto, at least in its first two movements. The third is a gavotte that could have come from Prokofieff. Walton, however, takes bigger breaths and speaks of bigger things, no matter how lyrically. While the Gardner concerto hints at deep emotions just around the corner, we never really turn the corner.

That said, the Third Symphony stands in marked contrast to everything else on the disc. In three movements (sonata/aria/sort-of rondo), it tells us that Gardner's no flyweight or at least not merely a confectioner. It speaks clearly of serious things. Yet, it doesn't inflate what it says. Gardner's habits of economy and elegance carry over. Unlike, say, Vaughan Williams symphonies, it doesn't overflow, it doesn't set to break your heart with too much beauty. But every phrase is beautifully shaped, every idea first-rate and memorable, some even surprising. The first movement is a little Mahleresque march, although on a far smaller scale. The Adagio, gorgeously singing, retains a wonderful coolness, a poise, a classical sense of moderation. The rondo, on two themes, bubbles and dances, as bits of the first movement peek through. A lot goes on, and Gardner keeps the traffic straight.

The Prelude for Strings has a tune that wouldn't have been out of place in a Mahler adagio, but, at under three minutes, it leaves the impression that it owes you some music. In other words, the tune begs for expansion. After its first period, I started hearing all sorts of Mahlerian extensions in my head, which of course never appeared. What Gardner has written is beautiful. He should have written more. This is Not Outstaying One's Welcome to a fault.

On the other hand, the Sinfonia Piccola for Strings is perfectly proportioned. A highly sophisticated essay, it brings to mind Tippett's Little Music for Strings, but without the latter's self-conscious Classical references. It plays masterful contrapuntal games. The second subject of the first movement gets brought back in inverted form during the recap. The second-movement passacaglia uses a modulating bass line, the first time I've knowingly encountered such a beast. The big danger of the passacaglia normally lies in the fact that one modulates with difficulty, while keeping the same bass line, since most bass lines don't modulate. I can't think of a single instance in Bach, for example. Sometimes a composer will use a bass of ambiguous tonality – usually one that finds itself at home in a "home" minor and its relative major. But the fact that a passacaglia normally stays in the same key gives the opportunity for a piece that builds in power. However, a badly-written passacaglia can bore the scuppers out of you. The tonal sameness can become exasperating. Gardner's "solution" – which, by the way, doesn't make things any easier for himself – just blows my mind. The quick third movement, a rondo with two themes, plays with stretto, canon, and fugato. Yet it sounds not academic, but high-spirited.

The little Irish Suite is a great deal of fun, although not especially distinguished or personal, as something like Malcolm Arnold's Irish Dances are. It's superbly made, if a bit anonymously. You feel as if any great craftsman could have done it. In five short movements, it uses both traditional and original tunes. Of the traditional tunes, I recognized exactly one: the second-movement "War song," "Avenging and Bright." The fourth-movement "Spring song," a Gardner original, sounds to my ear the most Irish melody in there. Not bad for a boy from Manchester. Or perhaps I could most easily imagine an Irish singer singing it. The finale, "Reel," sparkles with a Grainger-like energy (two original Gardner melodies among the authentic here as well). I would say this work as a whole lies closest to the main corpus of British light music. But five minutes after the final cadence and your enthusiastic applause, you'll probably forget all about it.

I congratulate AS&V for bringing this disc out. Gardner deserves a closer look than most recording companies have been willing to take. Sutherland and the Royal Ballet Sinfonia do a thoroughly professional, if not visionary, job.

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz