The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Schubert Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

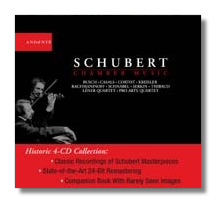

Franz Schubert

Chamber Music

- Trio for Piano & Strings #1 in B Flat Major, D. 898, Op. posth. 99

Alfred Cortot, piano; Jacques Thibaud, Violin; Pablo Casals, cello 1926 - Quintet for Piano and Strings in A Major "Trout", D. 667, Op. 114

Artur Schnabel, piano; Alphonse Onnou, Violin;

Germain Prevost, viola; Robert Maas, cello; Claude Hobday, bass 1935 - Fantaisie for Violin and Piano in C Major, D. 934, Op. posth. 159

Adolf Busch, Violin; Rudolf Serkin, piano 1931 - Trio for Piano & Strings #2 in E Flat Major, D. 929, Op. 100

Adolf Busch, Violin; Hermann Busch, cello; Rudolf Serkin, piano 1935 - Sonata for Violin in A Major "Grand Duo", D. 574, Op. posth. 162

Fritz Kreisler, violin; Sergei Rachmaninoff, piano 1928 - Quintet for Strings in C Major, D. 956, Op. posth. 163

Pro Arte Quartet: Alphonse Onnou & Laurent Halleux, violins;

Germain Prevost, viola; Marcel Maas & Anthony Pini, cellos 1935 - Sonatina #3 for Violin and Piano in G minor, D. 408, Op. posth. 137 #3

Jacques Thibaud, violin; Tasso Janopoulo, piano 1944 - Sonatina #1 for Violin and Piano in D Major, D. 384, Op. posth. 137 #1 - Rondo

Jacques Thibaud, violin; Tasso Janopoulo, piano 1944 - Octet in F Major, D. 803, Op. posth. 166

Léner Quartet with Hobday, Draper, Hinchcliff, Brain 1928

Andante 1990 (includes #1991-1994) ADD monaural 4CDs: 65:47, 59:37, 64:55, 64:10

The relatively newly born Andante project includes a classical music magazine, an international concert calendar, several web channels of streaming classical music, and CDs available for purchase. Over the next ten years, Andante's CD label plans to release approximately 1000 discs, with a focus on historical recordings. The packaging is lush. Essentially a small hardbound book, each release contains pockets for the CDs much as old 78rpm sets contained pockets for the shellac discs. The excellent digital remasterings are affected by a process that Andante is calling CAP 440. This process is dependent on the acquisition of the best source material available, optimal matching of records with playback styli, maintenance of an appropriate playback speed, 24-bit digital remastering, and CEDAR noise-reduction techniques.

To generalize, this set of Schubert's best chamber music (no "Death and the Maiden" Quartet, though!) can be divided into performances that use Schubert's music as a forum for intensely personal virtuosity, and performances that use virtuosity as a means to get to the core of Schubert's intensely personal music. An example of the former can be heard right at the start of the set. Neither Violinist Jacques Thibaud, cellist Pablo Casals, nor pianist Alfred Cortot ever were accused of facelessness, nor of sacrificing their individuality to the quest for textual perfection. Together, they made a predictably volatile trio, and hearing their work together is like listening in on the conversation of three opinionated conversationalists. Their topic: the heavenly Schubert, and Schubert gets peered at and turned over and around like a fine objet d'art in the process. Their recording of the First Piano Trio doesn't offer unanimity. Instead, it presents the listener with the sensation that this work is being created anew. There's little classicism here; Schubert is portrayed as a heaven-storming Romantic in a reading that thunders and sulks.

Without the competition/collaboration of Casals and Cortot, Thibaud is more straightforward in Schubert's sonatinas. He plays them with supreme confidence – with intensity, but without the unnecessary addition of darker emotions to their masculine charm. Thibaud shows that Romanticism doesn't always mean Sturm und Drang. Pianist Tasso Janopoulo, in no way deferential to Thibaud, seems to share the same interpretive personality, and his pianism is similarly confident.

With Thibaud, Casals, and Cortot, you remember the performance. With the Busches and Serkin, you remember the music. Which is more valid? The answer is that these approaches can be equally valid, and it is up to the performers to justify, artistically speaking, the musical choices they make. The musicianship of Adolf and Hermann Busch (violin and cello, respectively) and pianist Rudolf Serkin is more restrained. When they played together, they aimed for a unified style and unified expression. Textually, they are more faithful to Schubert – but of course the text alone doesn't tell the whole story to musicians or to listeners. In the Second Piano Trio, their smaller-scaled playing intensifies the music's pathos. A telling moment comes in the Finale, when the cello takes over the poignant melody last heard in the second movement. Hermann Busch plays it very "straight," and his restraint is more expressive than any big gesture would have been. "Tasteful" is a word that seems like damning with faint praise, but tastefulness blesses this reading. Adolf Busch and Serkin's collaboration on the C-Major Fantasie is similarly fine, although this work lacks the emotional depth of the Second Trio. Busch's violinism is strained by the music, particularly in the last movement, but his self-effacing artistry nevertheless makes a convincing case for it. These Busch and Serkin interpretations, while they don't blast Schubert into the late 19th century, do emphasize the composer's classicism.

The meeting of Fritz Kreisler and Sergei Rachmaninoff in Schubert's "Grand Duo" Sonata is like the encounter of two supermodels on the same runway. Kreisler, the most old-fashioned (stylistically speaking) of the violinists in this collection, slides from tone to tone more than most listeners would find acceptable today. If, however, one can get around the sliding and the occasional oddities of intonation (again, more stylistic and expressive than anything else), one can't avoid acknowledging that his sound, overall, is luminous, and that his musicianship is sometimes playful, sometimes inward-looking, but always committed. Rachmaninoff, one of the 20th century's great piano virtuosos, is touchingly content to support Kreisler – he doesn't want to set the music on fire. Nevertheless, one's ear is continuously attracted to the precision of his playing and to the purity of his tone.

Artur Schnabel, seldom a note-perfect pianist, nevertheless made his performances of Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert "perfect enough" through his coordination of fingers with stylistic savvy, and with pianistic soul. His interaction with members of the Pro Arte Quartet and double bassist Claude Hobday created a "Trout" Quintet whose colors and sparkle are as bright today as they were in 1935. Part of what makes this recording so memorable is the way that phrases and musical "paragraphs" ebb and flow; this is how the great actors deliver their Shakespearean speeches. Again, hearing this performance is like hearing a conversation between five friends who are well-spoken, compassionate, and emotional, yet never mastered by their emotions.

The Pro Arte Quartet (plus cellist Anthony Pini) contributes a C-major Quintet whose first two movements ensure the work's place in the empyrean. This is done, in part, through a meticulous matching of details as small as the speed and amplitude of vibrato. This is immediately noticeable, particularly if one compares this recording to any other recording of the same work. Furthermore, the poignant contrast between strength and fragility, implicit in the score, is explicitly realized by the musicians. Even when it is loud, the playing is of the most intimate nature. Unfortunately, I find their interpretations of the last two movements to be too heavy; the slow tempos and the vehemence of the bowing seem wrong for Schubert.

This set closes with a performance of the great F-major Octet that really does seem perfect: joyous musicianship is put to the service of (essentially) joyous music. Some performances of this work make one feel that the wind instruments (clarinet, bassoon, and horn) and the strings (string quartet and double bass) are in competition with each other, and that communication between the two instrumental groups is, if not adversarial, at least limited. Here, with the Léner Quartet and friends, the musicianship is warmly amicable and interactive. Individual personalities are neither inflated nor repressed, and Schubert's music, more than just a vehicle for virtuosity, becomes a topic for discussions of the most intelligent and emotionally involved kind.

As with the earlier Andante set of Beethoven piano concertos (Andante 41022-25), the transfers from 78-rpm compare very favorably with earlier work done by the other labels. Andante's transfers are consistently fuller, more wide-ranging, and quieter than can be heard elsewhere. For example, EMI Références CDH 7 61014 2 contains the Busch, Busch, and Serkin recording of the Second Piano Trio, but EMI's transfer makes the music seem almost emotionless, when compared to Andante's. Even the earliest discs, such as the 1928 recording of the Octet, sound surprisingly modern here.

Collectors who care about this music and these vintage recordings – and there are plenty who still do care! – will rightly consider this Andante release a rare treat.

Copyright © 2002, Ray Tuttle