The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Hanson Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

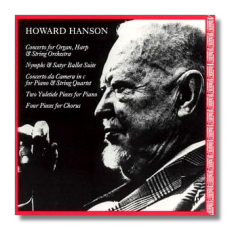

Howard Hanson

American Romantic

- Concerto for Organ, Harp, and String Orchestra (1926/rev. 1941)

- Nymphs and Satyr Ballet Suite (1979)

- Concerto da Camera in c for Piano and String Quartet (1917)

- Two Yuletide Pieces for Piano (1920)

- a Prayer of the Middle Ages (1976)

- Psalm 8, How Excellent Thy Name (1953)

- Psalm 121, I Will Lift Up Mine Eyes (1967)

- Psalm 150, Praise Ye the Lord (1965)

David Craighead, organ

Eileen Malone, harp

Brian Preston, piano

Meliora Quartet

Roberts Wesleyan College Chorale/Robert Shewan

Rochester Chamber Orchestra/David Fetler

Albany TROY129

I find simplicity harder to understand than complexity, oddly enough. Bach makes things easier for me than Mozart does, Arnold Schoenberg easier than Francis Poulenc. Perhaps musical technique counts for so much, and technical understanding comes down to a matter of books and exercises. To me, melody, among other things, lies outside technique, and so it's usually harder to write about, say, Puccini than about Wagner. In the case of Wagner, you can talk about other things, but there's little point discussing Puccini if you're not prepared to speak about his melodies.

Howard Hanson falls into that folder for me. I've blown hot and cold over his music for years, precisely because the technique, while masterful, is so beside the point of the music's appeal. Furthermore, of his seven symphonies, I really like only the sixth, the maverick among them, but then I have a bit of a problem grasping Sibelius's symphonies – which seem Hanson's model – as well. When I fail to connect, it's usually because I find him too genteel or, more rarely, that the technique fails to realize the implication of the musical ideas. Finally, despite lovely music of great individuality (one recognizes the Hanson sound-world after a few measures), Hanson seems a bit outside of everything, and that disturbs me. Like Alan Hovhaness, he has built his own mansion, but out in the middle of practically nowhere. By way of contrast, Aaron Copland – with a style just as individual – seems in the thick of modernism, as does even a neo-Romantic like Samuel Barber. You can imagine these two eating dinner with Stravinsky, Bartók, Hindemith, and Schoenberg. Hanson and Hovhaness pretty much dine alone.

Still, the individual work matters most, and the disc presents several of great beauty, from many periods of Hanson's career. The works listed above, from the concerto to the Yuletide Pieces, appeared previously on a Bay Cities CD (BCD-1005), but I welcome the bonus of the four choral works.

As he did with much of his output, Hanson cast the Organ Concerto in a single movement but, as usual with such things, clearly marked in four large subsections, corresponding to first movement, scherzo, slow movement, and finale. Hanson uses cyclical procedures, rather than sonata form, as well as ingenious constant thematic variation. The entire concerto grows out of an upward fifth and a modal run up the scale, both heard at the very beginning. It's a small field, of course, but this is one of the finest organ concerti ever – big ideas, long sweeping phrases, and canny treatment of the organ as a solo concertante instrument, rather than as an extra orchestral color with occasional solos. Hanson writes an heroic part, including a fiendish cadenza for the pedals. David Craighead not only hits the notes but conveys the architecture of the piece and carries up the listener in the emotional surge – a marvel of a performance. The Rochester Chamber Orchestra and conductor Fetler support him superbly well. This is a performance where ensemble and soloist feed off one another. I wouldn't be surprised if the ensemble had a few ringers from the Eastman School. The string sound is so Eastman, it recalls the old Mercury LPs with Hanson conducting.

The lush opening measures of Nymphs and Satyrs require a suspension of disbelief: Hanson first intended the music for solo clarinet. The piece yet again is flat-out gorgeous, but its very lyricism militates against anyone dancing to it. As a composer, Hanson sings rather than dances. To me, it's a tone poem in three short movements, the most delightful being the scherzo second movement. Hanson invented the main theme as something to serenade his dog Mollie with while he fed her dog biscuits. It's just one of those tunes that aren't constructed so much as they are found, and, by the way, it resembles both the dance of the Seven Dwarves in the Disney cartoon as well as the "Jodelling Song" from Walton's Facade. Fetler and his players give the work a very loving performance indeed.

The earliest work on the disc, the Concerto da Camera, sounds it. Hanson became more concise as he got older, and by the 1920s had cleaned up his scoring quite a bit. Here, he confuses power with the number of lines, a mistake he got over quickly. Still, the piece has its share of great themes (Hanson recycled one of them for his Fantasy Variations on a Theme of Youth at least thirty years later), but the composer can't seem to get the most mileage out of them. He even resorts to fugato (Stefan Wolpe described fugato, only half-jokingly, as what to do when you run out of ideas). The quartet plays heavily, and Brian Preston, on the piano, seems divorced from the proceedings.

As a pianist, Preston comes off better in the Two Yuletide Pieces. These have no specific program, much less one to do with Christmas. Still, Preston's difficulties arise from the character of the works themselves. They suffer from "fish-and-fowl." On the one hand, they are short salon morceaux, of the secondary kind tossed off by John Ireland and Arnold Bax when they weren't writing something important. On the other hand, the ideas seem to demand larger treatment. The piano writing is capable, but not sufficiently interesting in itself. I know, lighten up.

The choral music, on the other hand, is pure joy. A Prayer of the Middle Ages, for 8 parts a cappella, is an unusual combination for Hanson. In fact, it's the only example in his catalogue. For a composer of major works for chorus and orchestra (my favorite: the Lament for Beowulf), Hanson avoided the a cappella choir. In fact, the remaining works are for choir and organ. The Prayer brims with declamatory vigor and very rich chords. The choir's intonation teeters a bit (some of those chords sound a bit too rich due to pitch spread), particularly in the opening, where a written perfect fifth sounds like something other.

I first heard Hanson's Psalm 8 in the 60s sung by, believe it or not, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, who actually managed to get through it on their New York World's Fair album. Thank God for the accompanying organ. On the other hand, the organ part is necessary only for choirs that can't keep pitch. It adds very little to the musical texture. I wish someone would experiment with leaving it out. This is a major Hanson work, too seldom heard, one that managed to linger in my musical memory for thirty years. Hanson has left most of his compositional fingerprints all over the work: the quiet opening, the upward modal runs, building to a great climax on "What is man, that Thou art mindful of him," and ending in a radiant chorale-like passage (Hanson later appropriated this theme for his 4 Psalms for baritone and strings). By me, it's a major 20th-century choral work. The choir's pitch problems have largely cleared up, and their diction is admirable. It's a good performance, but once in my life I'd like to hear a professional group tackle it with the subtlety of shading and dynamic the work cries out for.

Psalm 121 is an extended baritone solo with organ accompaniment and choral interjections. Hanson's cantabile belongs to him alone. If you know anything of his opera Merry Mount, you've heard it. For that matter, you hear it in the Organ Concerto as well. It depends quite a bit on sequence, particularly on cadential figures, to build to climaxes. Again, the college kids do fine, but it would be nice to hear the darker, more ringing sound of grownups, particularly in the solo.

Again, I first heard Hanson's Psalm 150 from the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, this time from a mid-70s LP of mostly forgettable stuff. The poor surroundings only enhanced its quality. The College Chorale does better than the MTC, reaching a brave climax indeed on the alleluias.

John Proffitt, the recording engineer, not only has produced a fine set of field recordings, but also provided the very informative album notes. A superior job all around.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz