The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Schubert Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

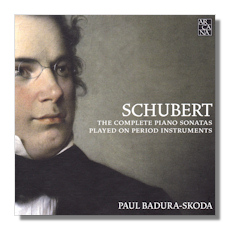

Franz Schubert

Complete Piano Sonatas

Played on Period Instruments

- CD 1

- Piano Sonata #1 in E Major, D. 157

- Piano Sonata #9 in B Major, Op. posth. 147 (D. 575)

- Piano Sonata #2 in C Major, D. 279

- CD 2

- Piano Sonata #5 in A Flat Major, D. 557

- Piano Sonata #10 in C Major, D. 613/612

- Piano Sonata #7 in E Flat Major, Op. posth. 122 (D. 568)

- CD 3

- Piano Sonata #6 in E minor, D. 566

- Piano Sonata #14 "Reliquie" in C Major, D. 840

- CD 4

- Piano Sonata #3 in E Major, D. 459

- Piano Sonata #15 in A minor, Op. 42 (D. 845)

- CD 5

- Piano Sonata #8 in F Sharp minor D. 571

- Piano Sonata #16 in D Major, Op. 53 (D. 850)

- CD 6

- Piano Sonata #4 in A minor, Op. posth. 164 (D. 537)

- Piano Sonata #17 in G Major, Op. 78 D. 894

- CD 7

- Piano Sonata #11 in F minor D. 625

- Piano Sonata #18 in C minor D. 958

- CD 8

- Piano Sonata #13 in A minor, Op. posth. 143 (D. 784)

- Piano Sonata #19 in A Major, D. 959

- CD 9

- Piano Sonata #12 in A Major, Op. posth. 120 (D. 664)

- Piano Sonata #20 in B Flat Major, D. 960

Paul Badura-Skoda, fortepiano

Arcana A364

The current catalog has several highly creditable complete cycles of Schubert's 20 or so solo piano works. Many of these are excellent. There are also many equally excellent single or paired-work CDs. This nine-CD set on Arcana by Paul Badura-Skoda is a little special, though.

In the first place, Badura-Skoda's intimate and continually refined expertise in his relationship with Schubert and the composer's piano music must be mentioned. Born in 1927 (in Vienna), the pianist won first prize in the Austrian Music Competition 20 years later. Performing with many of the most prominent and respected conductors in post-War Europe, Badura-Skoda specialized in the composers of the First Viennese School, producing and overseeing editions of both Mozart and Schubert. His discography is extensive.

Then, these are all period instrument performances.

Badura-Skoda uses only Viennese fortepianos from Schubert's time, or a little later: a Donath Schöfftos (c.1810); a Georg Hasska (c.1815); Conrad Grafs 432 (c.1824) and 1118 (c.1825); and a J.M. Schweighofer (c.1846). Each is carefully selected for between one and half a dozen or so recordings on the set. All are also in the pianist's own collection. Notably, each has a much more distinct personality than would be the case with modern pianos… the Graf 1118 used in D 557 [CD.2 tr.s 1-3] is much throatier than the Schöfftos for the lighter D 157 [CD.1 tr.s 1-3]. Indeed, the former is well-suited to the later sonatas, D894 [CD.6 tr.s 4-7] and D 960 [CD.9 tr.s 4-7]. At the same time, the changes in timbre, particularly, and also of attack, responsiveness and tone – mellow, fruity, tangy, pleasantly strident, almost plaintive, crisp, concentrated, decisive, shy – of Badura-Skoda's forte pianos becomes one of the cycles most attractive features. One suspects that even advocates of period keyboard performance may be pleasantly surprised by the way different fortepianos sing, lament, exclaim, declaim and use vast ranges of reserve and projection.

All these recordings were made between 1991 and 1996 in one of four Viennese locations which aptly suit this intimate yet extraordinarily profound music. So sound quality is important. The engineers at Outhere have done a great job of capturing the closeness and rapport between player and music. The expectation – justifiably – seems to have been that this is solo music calmly projected to closely attentive listeners as though the whole world were contained therein.

The beauty of the pianos' musicality is entirely unobstructed by any kind of extraneous mechanical or acoustic sound. At the same time, these are real instruments played with a range of appropriate dynamics. Listen to the pianos and fortes in the Second Sonata (D 279, paired with 346) [CD.1 tr.s 8-11], for instance, with the extraordinary extra percussive effects: the delicacy of Schubert's melodies is not compromised by the high volume implied by those moments in the allegretto.

This superb balance obtains throughout all performances on this set. It's as though we're in the room with Badura-Skoda. And that implies that we're experiencing the music of Schubert in ways close to those in which the composer might have wished us to hear it had he sat down to play it for us. This strips away anything heroic; yet maintains all the romanticism and enchantment of Schubert's conceptions.

Badura-Skoda's playing is neither overly romantic nor routine. It has, though, great sensitivity and great authority. His lightness of touch (evident, for example, in the opening Moderato of Number 10 (D 613/612) [CD.2 tr.4]) is matched by a strong and developed sense of the immense depths in Schubert's writing. And not just the melancholy, the wistfulness and famed "valedictory nature" of the late sonatas. The tempi always reflect and enhance the phrasing. But they allow the greater overall melodic coherence to emerge. There is never, for example, too great a set of contrasts between predominantly slow and and predominantly fast passages (and movements) merely because of the contrast. Badura-Skoda allows the music to lead us from musical stance to musical stance. Not from mood to mood.

The playing is precise without lacking spirit and a purposeful sense of direction. Technically brilliant, of course, the sonatas are as much moulded under and in Badura-Skoda's hands as they are revealed by an expert magician. Add to this the highly pleasing sonorities of the fortepianos and – as should be the case – it's the music itself that one remembers as much as the performance. Although one knows that Badura-Skoda must be implicitly commenting on each note, phrase and passage (his experience is too great for him not to), such "comments" are as modest and gentle as they are well-informed. At the same time, there is no sense of self-effacing gentility. Rather, of an ally, an advocate for Schubert meticulously going to work and standing back as things proceed and with almost the summative yet unobtrusive joy of which Brendel was so capable.

As said, the acoustic production is very good. It's resonant in varying degrees depending on the locale. In a series of performances by a single pianist this has the analogous advantage of variety to the multiple instruments employed. The acoustics have atmosphere and aid the sense of presence in the playing.

Online is a beautifully-produced 200-page PDF with nicely-detailed notes, essays on each work, and Badura-Skoda's rationales for approaching them as he has. An invaluable guide. One can learn a great deal about the corpus just from following what the pianist has written while listening to each sonata.

This is indeed a remarkable release. Yes, the recordings are 20 years old. No, those who respond to the sheen of Romanticism which can accompany some "luxury" accounts particularly of Schubert's later sonatas will probably find the honesty and transparency of the fortepiano not entirely to their taste. But for depth, insight, beauty, authenticity and a penetrating interpretation of Schubert's world, this set has the makings of a very significant one.

Copyright © 2013, Mark Sealey